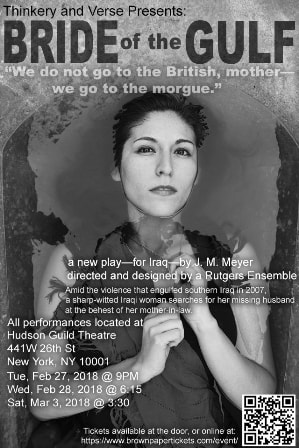

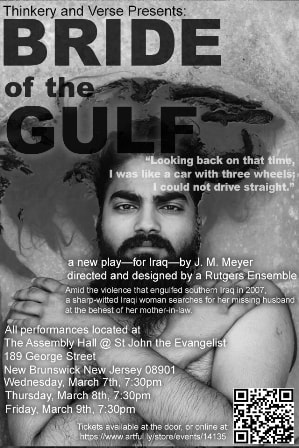

| Bride of the Gulf will preview for a limited run of six performances in New York and New Jersey in the spring of 2018. The first three shows will occur in Manhattan on: Tuesday, February 27th, 9pm Wednesday, February 28th, 6:15pm Saturday, March 3rd, 3:30pm These three performances will be a part of Winterfest @ Hudson Guild Theatre, 441W 26th St, New York, NY 10001. The play will then preview in New Brunswick, New Jersey at the Assembly Hall of St. John the Evangelist, 189 George Street, New Brunswick, New Jersey. The New Brunswick shows will occur on: Wednesday, March 7th, 7:30pm Thursday, March 8th, 7:30pm Friday, March 9th, 7:30pm Tickets are now available through Artful.ly ticketing services. In August 2018, Thinker & Verse plans to bring "Bride of the Gulf" to the Edinburgh Fringe for its international debut. |

|

0 Comments

Hi Johnny,

My name is C. Stephenson--I met you briefly during one of your visits to Lawrence. Anyway, I am the dramaturg for the B'srd Shrts and I am currently compiling playwright bio's for the program, and we thought it would be kind of snarky to do an interview format for your bio, since you are alive. (Also, I know Churchill is alive... but I can only manage so much :]) If that is okay with you, I was wondering if an e-mail format for the interview would be okay, as I'm not sure I could set up a phone interview quickly enough. If so, let me know and I'll e-mail you back a document with the questions that you can fill in. Also please feel free to add anything pertaining to yourself as a playwright or simply as a person that you would like to be included. I have a small bio from Kathy and Tim I've looked at so hopefully I'll be able to cover a good amount. Thanks, C. Stephenson --------------------------------------------------------------------- Hi C., Why don't you fire away, and we'll see how it goes? J. M. --------------------------------------------------------------------- Thanks for the quick response. Alright, firing away: Q: Okay, I have to ask the typical protocol bio question of: Where were you born, when were you born, where did you grow up and does that or your family have any influence on your writing/authorship? Q: Favorite playwright? Favorite absurdist playwright? Q: What style is your typical go to style for playwrighting, or do you take the Churchill/Beckett “can’t categorize me” approach? Q: Thanks for serving in the military— I have the utmost respect for you, I come from a long line of servicemen. How much does that influence or seep into your dialogue/themes? I can’t imagine a life experience at that caliber not finding its way into your art in some way. I am a new mom and I find even when I try not too, essences of that find their way into my scripts. Q: What’s your biggest pet peeve in life or as an artist? Q: Would you rather go to lunch with Samuel Beckett or Artaud? Care to explain? I think each would provide polarizing opposite effects. Q: Can you give a little overview of your process and approach to Cryptomnesia, or would that be a disservice to the show itself? Was there an object, idea, movement, etc. that influenced the creation? Q: Do you have a hidden talent? Q: If you could trade places with any person in history, dead or alive, who would it be? Such a lame question, but I think it says a lot. Q: Anything else you’d like to share? Thanks for baring with my horribly cliche questions, I didn't have adequate time to prepare a nice thoroughly thought out interview. I'll conduct a better one if you're around during production--keep it in the dramaturgy notebook. Thanks, C. Stephenson --------------------------------------------------------------------- Q: Okay, I have to ask the typical protocol bio question of: Where were you born, when were you born, where did you grow up and does that or your family have any influence on your writing/authorship? I was born in Dallas, Texas in 1982. I grew up in Dallas, New Orleans, and Kansas City. I am sure that my childhood shapes my plays. I am the oldest child in a family with three sons and three daughters. My parents are Roman Catholic, or at least what passes for Roman Catholicism in the United States. Social context and family play decisive roles in shaping who we are, but writing is more specific than living because with writing we can edit, revise, and manufacture our wares. A short play like Cryptomnesia can only share the smallest fraction of common ground with its playwright. Q: Favorite playwright? Favorite absurdist playwright? My favorite playwright, the playwright I spend the most time with, is Shakespeare. The tag 'absurdist' is more useful for audience members and critics than it is for the playwright or other artists; it helps audience members approach a piece with a certain wariness, and perhaps an openness to incredulity. One of my other favorite playwrights is Christopher Marlowe, Shakespeare's contemporary and stylistic predecessor; I suppose I adopt an 'absurdist' framework when watching his plays, which I usually enjoy. Of the twentieth century playwrights, the works of Samuel Beckett remain the most accessible thanks to the 'Beckett on Film' series. But if I have a preference for Beckett over, say, Churchill or Albee, that probably has more to do with convenience and accessibility than it does with aesthetics. Q: What style is your typical go to style for playwrighting, or do you take the Churchill/Beckett “can’t categorize me” approach? Do they say that? Or, from a creative place, do they simply find 'style' unhelpful? If Churchill labeled herself 'absurdist,' she might not have written plays like Top Girls or Serious Money. Q: Thanks for serving in the military— I have the utmost respect for you, I come from a long line of servicemen. How much does that influence or seep into your dialogue/themes? I can’t imagine a life experience at that caliber not finding its way into your art in some way. I am a new mom and I find even when I try not to, essences of that find their way into my scripts. What I saw and did in Iraq and Afghanistan alienated me from America. I mourn the disconnect between what we are, and what we could have been. I am very lucky, in that I have travelled through most of America, and much of the world, and have had the chance to respond to it. But when it comes to absurdism, I think it is more helpful to ask audience members, 'How do your own personal experiences shape your reaction what you are watching, listening, and feeling?' The playwright must be a little hands off; what we're making in Cryptomnesia is aesthetically closer to a mirror than to autobiography. It's not a landscape, or a character sketch, or a history. The fact that human beings are capable of observing absurdist theater and responding to it intelligently is almost a miracle. But however they respond to it, that response probably has more to do with who they are and where they are from than anything else. The artists and the playwright anticipate the audience, but cannot lead them with a hook or tether. Q: What’s your biggest pet peeve in life or as an artist? Distracted acting. Waiting for laughs. Carelessness with handguns. The incessant meowing of cats. Q: Would you rather go to lunch with Samuel Beckett or Artaud? Care to explain? I think each would provide polarizing opposite effects. Artaud has been dead much longer, and I think his advanced decomposition would be least likely to spoil my lunch. Q: Can you give a little overview of your process and approach to Cryptomnesia, or would that be a disservice to the show itself? Was there an object, idea, movement, etc. that influenced the creation? When Tim commissioned the play, he asked me to think about what 'absurdism' might mean to students at Lawrence University. Last fall, I had the chance to survey the campus, sit in on classes, and meet the students. I also explored the university's past, and tried to understand what it looked like to the people in the present. And, truth be told, I found I really liked Lawrence University. I had never been to a liberal arts college. I enjoyed the experience, and enjoyed observing what appeared to be the experience of the students and the professors. If absurdism involves some kind of confrontation with society--and I think it does--then my liking Lawrence presented a weird sort of dramaturgical problem. It took some work to get around that. Given the absence of obvious targets, I took a look at the individual 'person' who happens to be at Lawrence, and what they look like in the wider, less comforting society. Eventually I wound up with an observation, and two questions: As strong the local society might be, the individual is not necessarily able to remain in such a comfortable place. What might take them out of that society, and what are the personal costs thereof? That was the starting point. The starting point was a sort of complete McMansion; the next step was to destroy the roof, and tear out the drywall, and find out if anything was alive beneath the carpeting and inside the frame of the house. Q: Anything else you’d like to share? Yes, I suppose I would like to offer a few words about the other playwrights, and where I feel absurdism comes from. A popular definition of 'absurd' proposes 'crazy, unreasonable, untimely' as a suitable meaning for the word. The aesthetics of absurdism suggest mystery, confusion, and perhaps 'cutting-edge' theatrics, but the artists associated with absurdism spend an awful lot of its time looking mournfully backwards. Antonin Artaud named his theater after a French playwright of the previous generation (Alfred Jarry), and Artaud harvests his damaged characters from deep in the European past. Samuel Beckett pulls many of his images from the devastated landscapes of the Second World War, and his characters incessantly attempt to remember--remember what? a story? a person? How exactly did they tumble into their current situation? How can they get it right? How can they do it better next time? Whereas Artaud offers visual ecstasy and religious voyeurism, Beckett offers comic circles and tragic cynicism. As a whole, the plays of Caryl Churchill defy any particular emotional landscape, through she also looks backwards towards realism and naturalism. Her play This is a Chair seems to reference the late twenties French painting called La trahison des images. The painting shows us a pipe, but is helpfully labeled, Ceci n'est pas une pipe: "This is not a pipe." And of course the label on the painting is correct; it is not a pipe, but rather a painting. But This is a Chair. Churchill explores the spongy limits of realism, the darkness that surrounds the everyday people that democratic-capitalism panders to. The three writers--Artaud, Beckett, Churchill--find themselves in a crazy, unreasonable, untimely moment. Whatever it is that they were looking for in their youths, it was not quite there, and the experience of its absence granted no secret wisdom that can help the next generation do any better. Comic circles, tragic cynicism. Realism with spongy limits. Visual ecstasy and religious voyeurism. The techniques and mysteries of these writers trace back to the witches of Macbeth, Shakespeare's soliloquies, and the clipped in media res epics of Homer. But while these writers are decidedly Western in thought and action, one can also look further afield in the wide world and find theatrical art with a kindred spirit; the rhythmic mysteries of Noh drama come to mind, where the key 'event' of the play can involve an act listening, rather than an act of confrontation. There are others as well, but that's enough out of me. Do you remember the board game "Chutes and Ladders," where players take turns climbing the rungs of a ladder, only to slide back to square one over and over again? The makers of the game illustrated the board with children who, for good behavior, were shown climbing the ladder, and for bad behavior were sent sliding down the chutes. KILL FLOOR, the new play that just went up at LTC3, depicts modern poverty, where the ladders are missing the lower rungs, and the gleaming steel chutes of modern America provide the blind and driving illusion of progress all the way back to square one.

Marin Ireland delivers a star turn as 'Andy,' a newly released ex-convict. Desperate for a job, she signs on as slaughter-house employee, where she's quickly sent to the kill floor. Every thirteen seconds a bolt gun kills a cow, while another machine lifts the fresh carcass out of the pen and skins it--sometimes while the animal is not quite dead. Accidents are common, sometimes leading to more pain for the cattle, and sometimes injuries for the workers. The kill floor itself is kept just beyond our sight, but its implications bleed out into every aspect of Andy's life. Rick, Andy's affably manipulative and dangerously amorous boss (played by Danny McCarthy), tells her not to worry: her co-workers are Mexicans ("good workers...reliable") but because his bosses are "racist as hell," she's likely to get promoted above them and sent upstairs to do office work. As the Bard says, "All [wo]men have some hope," and some hopes are higher than others. Andy's desperation to find a job is rooted in her desire to provide for her biracial teenaged son, B, who is simply embarrassed by Andy's reemergence. B is understandably more interested in surviving high school and first-crushes than he is in bringing his estranged and needy mother back into his life. B remembers too well his mother's arrest, and Marin Ireland provides subtle, nervous gestures that suggest that Andy is still struggling with past addictions, though she insists otherwise to her boss. Instead of loving his mother, B reaches out to Simon, a white schoolmate and self-fashioned rapper. Simone lays out "sick rhymes" for the benefit of B. B helps Simon score weed. More importantly, the two are caught in an unequal and entirely believable sexual awakening. 'Coming out,' which is getting easier in much of America, seems a nihilistic social choice in their world, and their relationship stands tensely at the edge of discovery. The two young performers, Nicholas L. Ashe and Samuel H. Levine, fully own their characters; under the guidance of director Lila Neugebauer, they create the play's most dynamic, topsy-turvy moments; even if Koogler's insights on race, sexuality, and high school politics are not radically fresh, they are truthfully delivered with wit, grace, and daring. With B avoiding her, Andy hesitatingly looks for connection elsewhere. She first turns to Sarah (played by Natalie Gold), an outgoing woman from the right-side of the tracks; the relationship allows the play to show that the two women face similar emotional trials, but with such wildly different economic resources as to not be speaking the same language. Sarah thrives (and perhaps even applauds herself) for keeping Andy company, but Andy is unwilling or unable to broach her own past, and so their friendship is stunted. As that relationship stalls, Andy takes a turn into another dead-end by consenting to her married boss' request for a date. Abe Koogler, showing his chops for modern drama, begins many of his quick, short scenes in media res, with the relationships already established and understood by the characters, and the drama centered on each person's peculiar verbal strategies as they drive after their meager, vulnerable (and often funny) desires. He expertly writes in the staccato semi-fluency that thrives in America's small black box theaters. (Why, in American dramas about the economically disadvantaged, is there a shortage of eloquent, rhetorically powerful people saying stupid things? It must be a two-hundred year carryover from the imprinting excellence of Charles Dickens. But Mark Twain is our man, and he had plenty of characters who earnestly believed in the tomato paste they were selling.) At any rate, as with David Mamet and Annie Baker, each broken and partial sentence leaves room for our sympathies. The less the characters say, the more we root for them; the more they open their mouths, the more we know they lack the resources to thrive, and dash the hopes we have invented for them in their quiet moments. The set by Daniel Zimmerman (wide, shallow, and grey) works with Ben Stanton's lighting and Brandon Wolcott's sound to deliver the audience into an icy world where a slaughterhouse and budget apartment share the same colorless walls. Prison and slaughter are never seen, but always present. The actors dart in and out of the wings like cattle through chutes, and neither they nor we have much idea of what's coming next. The simplicity of the design invited the imagination into the world of the play, and ties together the disparate threads of the story, so that the voices and themes from one scene echo into the next. It is a play that disposes with an obvious ending, or a well-made play's denouement. Unlike in Annie Baker's THE FLICK (or Oscar Wilde's THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING ERNEST), there are no craftily hidden pieces of paper that cause the play to burst into a climax and a resolution. Most of Koogler's characters could struggle on, nearly unchanging, and constantly caught off-guard, for years and years. Rather than forcing a neat cap on the play's final moments, Koogler brings it to a close at the ninety minute mark, like the closing shift in a warehouse; the lights silently dim on an evening of open, honest, and throat-catching performances. KILL FLOOR depicts characters living in poverty; they prove likable, but they will not win. This play is a necessary stab in the eye to the Group Theatre's optimism at the end of the Great Depression. If the playwright senses hope, but sees little way out, then we should take his word for it, and thank him for his honesty: we should not request that playwrights invent neat little plots designed to satisfy our complacency. After his death, onlookers referred to Orde Wingate as a religious fanatic, an original thinker, and as a ruthless killer. Many of these charges stem from Wingate's time as the leader of the Special Night Squads. In 1938, in British Palestine, Wingate founded Jewish-British units called Special Night Squads; these units are now considered the forerunners of the modern Israeli Defense Forces. Many Israeli leaders, like Moshe Dayan, credited Wingate for inspiring Zionist leaders to adopt a more aggressive posture throughout British Palestine. None of these terms really apply to Wingate. Today, people speak of atrocities. But it is more helpful to understand what people are willing to do in the name of justice and against injustice. Wingate turned the secular Jewish partisans back to Gideon. The Special Night Squads were the formative event in the lives of some of the most important individuals in the history of Israel. No streets in Israel are named after Wavell or Dill. Some for Allenby, but most for Wingate. After Balfour, Wingate had the largest cultural impact on Israel. What did British, white, protestant, gentleman raised Orde Wingate think of the illiterate, tribal Arab farmers and shepherds? Very poorly.

In the years just prior to the Second World War, Wingate stumbled across an all too human problem in his own life, and came across what was a practical, if unexpected, solution. The solutions available to him depended entirely on previous life circumstances. As those solutions matured out of perceived necessity and into deliberate, planned action, their character--and the presumed character of their author--shifted, the way the sound of siren can sound different depending upon whether its vehicle is moving towards you, or moving away. In 1938, Wingate became a Zionist. Nothing about his previous experiences quite forecast his sudden determination to help European Jews establish a Palestinian homeland. We, in the twenty-first century, know of events that Wingate never lived to see, and so the word Zionism tastes clear and strong in our mouths, giving off flavors either bitter or sweet. For the British, the word lacked some (though not all) of its pungency in 1938. Here is the key fact to understanding Wingate's adoption of Zionism: It occurred in the company of his wife. He had sold himself as a man of action, and now had to prove it after months of relative indolence and sloth. The fallout from this impulse would bend (but not break) the Wingate marriage, and would permanently reshape their social and political interactions with their peers, followers, friends, and leaders. I have been thinking of poems about sailors over the past few days, and posting a copy of Tennyson's 'Ulysses' seems like the natural way to mark the process.

For me, the poem ultimately describes the social and psychological challenges of evading despair. When trying to avoid our own suffering, we often hurt those around us, as I think Ulysses does in this poem when he abandons his 'aged wife' and 'savage race;' he chooses to return to the ocean, and more importantly, into the wonderful unknown. He anticipates a rush of adrenaline, and a return to the adventures that occupied the twenty years that are partially depicted in Homer's Iliad and Odyssey. Ulysses' decision is a social challenge because he abdicates his responsibilities as a king, a father, and a husband; the monologue also suggests that he is rallying his sailors around him so that they can all continue the journey together--I wonder if anyone tries to remind them about the cyclops. Ulysses' decision is also a psychological challenge because his effort to revive his youthful mentality may very well fail. Is he still, as he promises, strong in will ? The poem's final iambic line strikes such a powerful rhythm that is almost impossible not to believe him. To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield. Tennyson, like us, may have found Ulysses' last line too seductive to find another ending. Ulysses BY ALFRED, LORD TENNYSON It little profits that an idle king, By this still hearth, among these barren crags, Match'd with an aged wife, I mete and dole Unequal laws unto a savage race, That hoard, and sleep, and feed, and know not me. I cannot rest from travel: I will drink Life to the lees: All times I have enjoy'd Greatly, have suffer'd greatly, both with those That loved me, and alone, on shore, and when Thro' scudding drifts the rainy Hyades Vext the dim sea: I am become a name; For always roaming with a hungry heart Much have I seen and known; cities of men And manners, climates, councils, governments, Myself not least, but honour'd of them all; And drunk delight of battle with my peers, Far on the ringing plains of windy Troy. I am a part of all that I have met; Yet all experience is an arch wherethro' Gleams that untravell'd world whose margin fades For ever and forever when I move. How dull it is to pause, to make an end, To rust unburnish'd, not to shine in use! As tho' to breathe were life! Life piled on life Were all too little, and of one to me Little remains: but every hour is saved From that eternal silence, something more, A bringer of new things; and vile it were For some three suns to store and hoard myself, And this gray spirit yearning in desire To follow knowledge like a sinking star, Beyond the utmost bound of human thought. This is my son, mine own Telemachus, To whom I leave the sceptre and the isle,-- Well-loved of me, discerning to fulfil This labour, by slow prudence to make mild A rugged people, and thro' soft degrees Subdue them to the useful and the good. Most blameless is he, centred in the sphere Of common duties, decent not to fail In offices of tenderness, and pay Meet adoration to my household gods, When I am gone. He works his work, I mine. There lies the port; the vessel puffs her sail: There gloom the dark, broad seas. My mariners, Souls that have toil'd, and wrought, and thought with me-- That ever with a frolic welcome took The thunder and the sunshine, and opposed Free hearts, free foreheads—you and I are old; Old age hath yet his honour and his toil; Death closes all: but something ere the end, Some work of noble note, may yet be done, Not unbecoming men that strove with Gods. The lights begin to twinkle from the rocks: The long day wanes: the slow moon climbs: the deep Moans round with many voices. Come, my friends, 'T is not too late to seek a newer world. Push off, and sitting well in order smite The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths Of all the western stars, until I die. It may be that the gulfs will wash us down: It may be we shall touch the Happy Isles, And see the great Achilles, whom we knew. Tho' much is taken, much abides; and tho' We are not now that strength which in old days Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are; One equal temper of heroic hearts, Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.  A scene from BASETRACK LIVE, a theater project that slices live performance with visceral footage of the war in Afghanistan, quiet conversations with military wives, and a powerful musical score. [Image taken from the BASETRACK LIVE website.] A scene from BASETRACK LIVE, a theater project that slices live performance with visceral footage of the war in Afghanistan, quiet conversations with military wives, and a powerful musical score. [Image taken from the BASETRACK LIVE website.] MCCULLOUGH THEATRE, TEXAS PERFORMING ARTS CENTER, AUSTIN, TEXAS: Three years ago, Texas Performing Arts Center (TPAC) brought us BLACKWATCH, a stage-play that explored how the history of the famous Blackwatch Royal Highland Regiment unfolded in the killing fields of modern Iraq, and how that history ultimately came to an due to a bureaucratic cost-cutting decision back in London. The show proved spectacular, and brought big-city virtuosity to Austin. Texas Performing Arts has now followed up on that success with the outstanding debut of BASETRACK LIVE, produced by Anne Hamburger and En Garde Arts. Created by Edward Bilous, directed by Seth Bockley and adapted by Jason Grote, this new play combines battlefield journalism, live performance, and disturbing interviews, and then exposes and explores the strange deprivations, honors, and hopes of the 1-8 Marines, a unit that has deployed and redeployed (time and again) since 2001. The play opens with short snippets of interviews with Marines in Afghanistan in the year 2010; each Marine says his name and names his home, and then his image falls into the distance and another Marine takes his place. Their voices rumble together (a cacophony of youth) as the onstage band, a four person unit, suddenly displaces the remaining silence of the auditorium; the music, directed by Michelle DiBucci, grants the multimedia images a sense of enduring strength. The exact mission in Afghanistan remains vague and purposeless, but the band's presence underlines the intention of the play: to honor the experience and challenges of the men and women serving in today's armed forces, often in wars that began just a few years after those men and women were born. The multimedia interviews slice back onto the stage, and introduce a new theme: the intentions of 'the few and the proud' who choose to become Marines. The interviews then give way to a live performer, Tyler La Marr, who portrays AJ, a Marine corporal that seeks to explain his own decision to join the Marine Corps, as well as his decision to become an infantryman, and his day to day experience of life in Afghanistan. The actor Ashley Bloom then enters the stage-light. She portrays AJ's wife, Melissa. Her face appears as a projected image in the heights above the stage. She tells her story to the camera of a laptop computer. A gauze curtain divides Melissa and AJ, just as the script divides their stories; AJ talks exclusively of war, while Melissa talks of AJ and the experience of his presence and absence in her own life. AJ mourns the death of a friend, while Melissa fears a knock on the door that may announce her husband's own violent death. AJ describes firefights and Oakley sunglasses, while Melissa describes giving birth to their only daughter. Painfully, AJ never mentions his wife, while Melissa's every word centers around her husband. A bullet puts an end to AJ's deployment, as it rips through his bicep and sends him home; the journey ends in a matter of days. Suddenly estranged from his unit, he disparages (and disdains) his estrangement from his wife. He seems to miss Afghanistan more than he ever missed her. Melissa recoils from AJ's violent outbursts, his drinking, and his destructive obsessions with handguns and rifles. The Marine Corps ends AJ's young career with a medical discharge; he carries with him memories of a painful past, an uncertain present, and a future with little hope. Melissa and AJ attempt couples' counseling, but it fails; the once happy couple can remember all the reasons that they hate each other, but not the source of their love. Melissa eventually leaves AJ. AJ finally drags himself to therapy for PTSD. The play concludes with hope, as the therapist tells AJ that "the hard part...is over, as of right now." BASETRACK is a superior example of 'verbatim' theater, wherein the artists lift the script from interviews conducted with real people. In this case, the real people are combat veterans from 1-8 Marines, a unit deployed to Afghanistan in 2010, and their wives. The show smartly centers on AJ, with a small cast of video interviews orbiting his experience. AJ works as a main character because he is smart enough to laugh at his own foibles, and honest enough to detail the challenges he has faced. The peculiar brilliance of the show stems from intersection (or lack thereof) between the narratives of AJ and Melissa. The script highlights the awful distance between spouses during a military deployment, especially for the very young. And so the play universalizes the story of AJ and Melissa by tracing the similarities between their experiences and those of their peers; BASETRACK LIVE presents a sort of multimedia triptych of live performance, music, and viscerally assembled videos and photographs. (The video designers were Sarah Outhwaite and Esteban Uribe. Their work represented the best use of video I have seen in Europe or America.) The voices of the women prove especially important. The play presents clips of interviews taken from Skype or Google Chat. Each woman, painfully young, describes the experience of waiting, day after day, for news both good and bad about their spouses deployed to Afghanistan; unfortunately, the journey of these young women does not get easier upon the unit's return. Medi, one of the wives, dances around the challenges she has faced: "You really have to be careful of what you say and how you present things. You know, like I said...[their] innocence is gone....Their whole way of thinking is completely different over there. That just affects how they respond to you when they come home." One of the limitations to verbatim theater is that it can only use the language that comes up in the interviews. If the interviewed veterans and wives avoid certain topics or perspectives, then the show must necessarily also avoid those topics. Verbatim theater holds a mirror up to nature, but cannot completely control the quality of the nature that enters its frame; just as the academic disciplines of ethnography and political theory often stress different dimensions of the same problems, so verbatim theater and 'regular' theater differ in their outcomes, though not necessarily in effectiveness. The use of multimedia and music helps BASETRACK LIVE overcome the limitations of verbatim theater, as these cinematic elements transform everyday language into poetry through the use of echo, repetition, and underlined sound. The band, which consists of the outstanding quartet of Trevor Extor, Kenneth Rodriguez, Mazz Swift, and Daniele Cavalca, elevates the play with relentless intensity--Schiller and Goethe would be pleased. If there is room for refinement, it might lie in the combat scene. AJ, the lead character, remembers a sudden unleashing of 'chaos.' But an American infantrymen, when pressed, can reveal a precision to a combat that consists of casualty reports, air support, covering fire, and fire commands, the sum of which grants combat the frightening (yet empowering) quality of a testosterone and adrenaline riddled blood-sport. This 'precision' in midst of seeming 'chaos' helps explain the willingness of soldiers to return to the fire time and time again. American soldiers, backed with taxpayer equipment, feel that they can win any firefight they stumble into (more often than not). And so the combat scene could use further exploration (but not too much). In regards to content, the play might also consider pointing out that an American soldier's pay increases dramatically when stationed overseas, thus enabling the purchase of expensive Oakley's, new pickup trucks, new tattoos, and guns, guns, guns once a soldier returns home. There are a also a few moments of humor that may require a little more direction in order to cue the audience that laughter is acceptable in a war story. But my complaints are mild, and my praise is strong. BASETRACK LIVE provides an intelligent, graceful way to empathize with the twenty-first century military experience. For a veteran like myself, it brought back surprising memories and shadows. It is a painful, sad place to go. The passages in which the soldiers contemplate suicide are particularly haunting, and open doors I prefer to keep locked and closed. But it is worth opening those doors to remind oneself that the war in Afghanistan, though perpetually 'winding down,' continues instead with perpetual cost. As it was in 2001, so it continued in 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, and 2014. The BASETRACK LIVE project must continue. One hopes the creative team might consider asking the Afghans, who have now fought against (and alongside) the Americans for thirteen years, what they think of us. With the exception of Hamid Karzai, it often feels that we have thought painfully little of them. BASETRACK LIVE shows us a video in which an Afghan woman screams at the presence of a video camera in her family home; I walked away from BASETRACK without much of an understanding of her pain, but that seems fitting in a portrait that emphasizes the 1-8 Marines and the struggles they face within their own homes upon returning from combat. The play is now on tour. Seek it out. I just saw a person pour appetite suppressant into their coffee. Is Plato happy, distressed, or simply unimpressed? Explain your answer in haiku.

Ernest Hemingway made the Iceberg Principle famous. When writing a story, he felt that a writer could strengthen it by omitting key facts or events. Omission can help people feel something more powerfully, rather than simply understanding it. It evokes eeriness and mystery, and (at best) curiosity rather than befuddlement. Hemingway took his method seriously enough to mention it in more than one book. In that way, he clued his readers in on how to read his work. He expected them to search for subtext and, later, to ask themselves why they were able to fill in the blanks that he created.

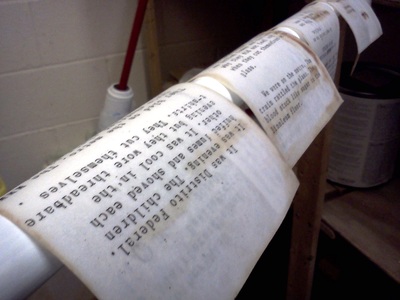

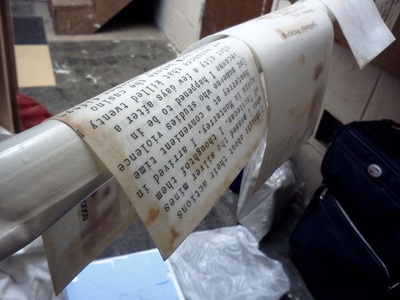

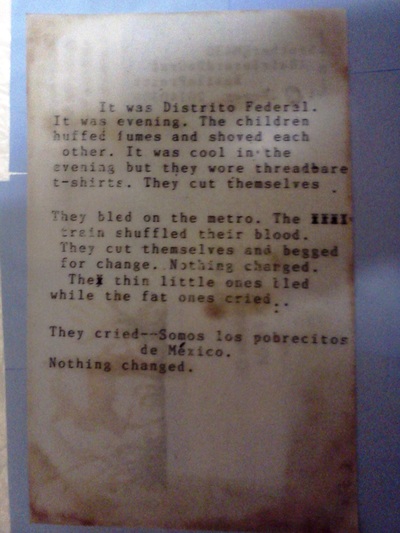

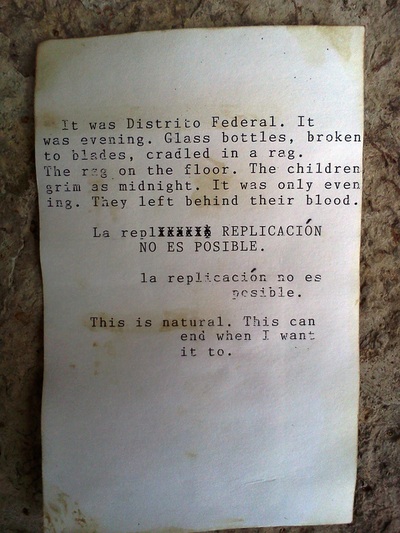

He uses the term 'iceberg' to visualize his approach in his story Death in the Afternoon. An iceberg floats about the surface of the ocean. A small portion is visible above the water. But its most significant mass remains beneath the surface. So then with good literary fiction: something vital must remain beneath the surface. The strength and power is beneath the surface, however explicit and powerful it may charge through the mind of the writer. Of course, Hemingway did not invent the idea of omission, though he popularized it as a deliberate tool. Shakespeare omits the title couples' sexual history in Macbeth, and omits a great deal of the father-son relationship in Hamlet. He never tells us where Feste the clown is returning from in Twelfth Night, and why he ever left the side of the grieving Olivia. Shakespeare did not invent omission either. Homer's epics examine only core of ancient myth, and leave out much besides. The Bible, especially the Old Testament, leaves much to mystery. Omission also appears in plays, like Terrence Rattigan's The Deep Blue Sea, and Kirk Lynn's new play Your Mother's Copy of the Kama Sutra. I won't express how Kirk Lynn's play uses it. Go to Playwrights Horizons and find out for yourself (closes May 11). In Rattigan's the Deep Blue Sea, the playwright never fully reveals source of sexual dissatisfaction between a separated couple. And he never reveals why an ex-medical doctor spent time in prison. In an odd way, the characters in Rattigan's play suffer from old-fashioned British restraint. But in Rattigan's hands it is a device that strengthens the story, rather than simply imitating mid-century British life. Omission is a powerful dramatic tool. I think, however, it's possible to go too far with the use of omission. It's not a fix-it device or a band-aid. Playwrights and directors and workshop-companies often describe a need for 'rough edges' and 'missing pieces.' These are necessary, but must be counterbalanced with the artists' responsibility to reveal us to ourselves--and to reveal themselves to us. Perhaps more importantly, the iceberg metaphor deserves another look. An iceberg is made of frozen water. Spin it, tumble it over, let it melt a little. As it floats in the water, most of the iceberg will remain submerged beneath the ocean surface. Only a narrow fragment will peak above. From the perspective of the iceberg (or its viewer) it does not much matter which part is submerged and which part is above the surface. It will look about the same. The difference between literary omission and an iceberg is this: it matters a great deal, when writing, what you leave below the surface, and what details you make explicit to your audience. Writing is not a frozen chunk of arctic. It is something wholly unto itself. The greater the writer, the better they know what to omit and what to state. It is an ultimate moment of craft. This week, I had the privilege of staying at Rubber Repertory's Pilot Balloon Church-House. My partner, Karen Alvarado, was scheduled to come with me, but she had to go to NYC over the weekend for auditions. I missed her presence. But her absence compelled me to write a piece that tracks the contours of our feelings for each other. I suspect I will post more about that in a few weeks. In the meantime, I wanted to share some images from a very small project I worked on while I was here. As a part of Rubber Repertory's fundraising efforts, they offered their donors the opportunity to receive a piece of postcard art from the artists staying with them in Lawrence. The postcards presented a challenge, as straightforward writing felt inadequate for the medium--I write postcards all the time, and would never classify those as 'art.' So I experimented with a few new methods, so to speak, to earn my keep. The images below don't tell half the story, but I hope they will help me remember the work. The postcards I made were inspired by a handful of Mexican youths I saw on the metro near the Autonomous University in Mexico City; I watched them cut themselves with bottle glass and beg for pesos--but the passengers gave them nothing. Here's a partial list of materials: postcard, brother EM430 typewriter, milk of magnesia, club soda, soap, distilled vinegar, a memory of Mexico, a broomstick, a shower, a ceramic baking dish, absorbent paper, and a fourteen gauge needle that I brought back from Iraq. Many thanks to Rubber Repertory's Josh Meyer and Matt Hislope! I was lucky to have the opportunity to visit them in Lawrence! I am going to miss them, and the intensity of openness with which they listen to human experience.

Glory be to God for dappled things – For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow; For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim; Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches’ wings; Landscape plotted and pieced – fold, fallow, and plough; And áll trádes, their gear and tackle and trim. All things counter, original, spare, strange; Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?) With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim; He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change: Praise him. Gerard Manley Hopkins alliterated experience into a strange, powerful new form of verse. As in many of his other poems, he uses Pied Beauty to alienate nature from the familiarity of the senses. The patterns on trout turn to 'rose-moles all in stipple' while clouds mottle the sky like the spots on a cow. He hides the poem's central theme--the varieties of human appearance and behavior--beneath the fig leafs of humility and the mysteries of God. He never uses the words 'human,' yet he cuts nature with human typologies and contradictions. You and I are the most 'counter, original, spare, strange' creatures that he knows; we are alternately 'swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim.' He could hold our fickleness against us, but he prefers to hold it a virtue and a grace. 'Praise him.'

I had heard this poem before, but it stumbled my way again at Rubber Repertory's Pilot Balloon Church-House, where it serves as their daily prayer. Many thanks to Josh and Matt for their hospitality! It's been a wonderful week in Kansas. |

AuthorJ. M. Meyer is a playwright and social scientist studying at the University of Texas at Austin. Archives

July 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed