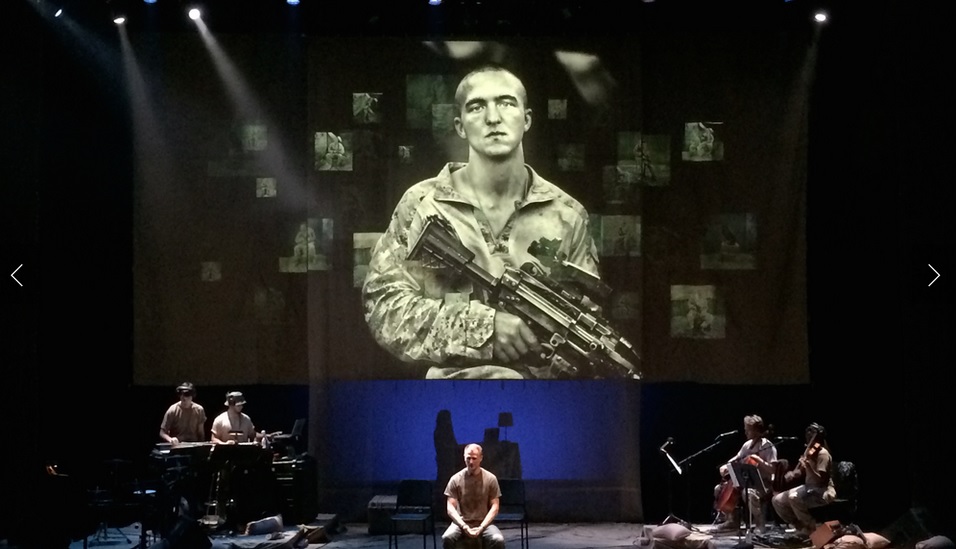

A scene from BASETRACK LIVE, a theater project that slices live performance with visceral footage of the war in Afghanistan, quiet conversations with military wives, and a powerful musical score. [Image taken from the BASETRACK LIVE website.]

A scene from BASETRACK LIVE, a theater project that slices live performance with visceral footage of the war in Afghanistan, quiet conversations with military wives, and a powerful musical score. [Image taken from the BASETRACK LIVE website.] MCCULLOUGH THEATRE, TEXAS PERFORMING ARTS CENTER, AUSTIN, TEXAS:

Three years ago, Texas Performing Arts Center (TPAC) brought us BLACKWATCH, a stage-play that explored how the history of the famous Blackwatch Royal Highland Regiment unfolded in the killing fields of modern Iraq, and how that history ultimately came to an due to a bureaucratic cost-cutting decision back in London. The show proved spectacular, and brought big-city virtuosity to Austin.

Texas Performing Arts has now followed up on that success with the outstanding debut of BASETRACK LIVE, produced by Anne Hamburger and En Garde Arts. Created by Edward Bilous, directed by Seth Bockley and adapted by Jason Grote, this new play combines battlefield journalism, live performance, and disturbing interviews, and then exposes and explores the strange deprivations, honors, and hopes of the 1-8 Marines, a unit that has deployed and redeployed (time and again) since 2001.

The play opens with short snippets of interviews with Marines in Afghanistan in the year 2010; each Marine says his name and names his home, and then his image falls into the distance and another Marine takes his place. Their voices rumble together (a cacophony of youth) as the onstage band, a four person unit, suddenly displaces the remaining silence of the auditorium; the music, directed by Michelle DiBucci, grants the multimedia images a sense of enduring strength. The exact mission in Afghanistan remains vague and purposeless, but the band's presence underlines the intention of the play: to honor the experience and challenges of the men and women serving in today's armed forces, often in wars that began just a few years after those men and women were born.

The multimedia interviews slice back onto the stage, and introduce a new theme: the intentions of 'the few and the proud' who choose to become Marines. The interviews then give way to a live performer, Tyler La Marr, who portrays AJ, a Marine corporal that seeks to explain his own decision to join the Marine Corps, as well as his decision to become an infantryman, and his day to day experience of life in Afghanistan.

The actor Ashley Bloom then enters the stage-light. She portrays AJ's wife, Melissa. Her face appears as a projected image in the heights above the stage. She tells her story to the camera of a laptop computer. A gauze curtain divides Melissa and AJ, just as the script divides their stories; AJ talks exclusively of war, while Melissa talks of AJ and the experience of his presence and absence in her own life.

AJ mourns the death of a friend, while Melissa fears a knock on the door that may announce her husband's own violent death. AJ describes firefights and Oakley sunglasses, while Melissa describes giving birth to their only daughter. Painfully, AJ never mentions his wife, while Melissa's every word centers around her husband.

A bullet puts an end to AJ's deployment, as it rips through his bicep and sends him home; the journey ends in a matter of days. Suddenly estranged from his unit, he disparages (and disdains) his estrangement from his wife. He seems to miss Afghanistan more than he ever missed her. Melissa recoils from AJ's violent outbursts, his drinking, and his destructive obsessions with handguns and rifles. The Marine Corps ends AJ's young career with a medical discharge; he carries with him memories of a painful past, an uncertain present, and a future with little hope.

Melissa and AJ attempt couples' counseling, but it fails; the once happy couple can remember all the reasons that they hate each other, but not the source of their love. Melissa eventually leaves AJ. AJ finally drags himself to therapy for PTSD. The play concludes with hope, as the therapist tells AJ that "the hard part...is over, as of right now."

BASETRACK is a superior example of 'verbatim' theater, wherein the artists lift the script from interviews conducted with real people. In this case, the real people are combat veterans from 1-8 Marines, a unit deployed to Afghanistan in 2010, and their wives. The show smartly centers on AJ, with a small cast of video interviews orbiting his experience. AJ works as a main character because he is smart enough to laugh at his own foibles, and honest enough to detail the challenges he has faced.

The peculiar brilliance of the show stems from intersection (or lack thereof) between the narratives of AJ and Melissa. The script highlights the awful distance between spouses during a military deployment, especially for the very young.

And so the play universalizes the story of AJ and Melissa by tracing the similarities between their experiences and those of their peers; BASETRACK LIVE presents a sort of multimedia triptych of live performance, music, and viscerally assembled videos and photographs. (The video designers were Sarah Outhwaite and Esteban Uribe. Their work represented the best use of video I have seen in Europe or America.) The voices of the women prove especially important. The play presents clips of interviews taken from Skype or Google Chat. Each woman, painfully young, describes the experience of waiting, day after day, for news both good and bad about their spouses deployed to Afghanistan; unfortunately, the journey of these young women does not get easier upon the unit's return.

Medi, one of the wives, dances around the challenges she has faced: "You really have to be careful of what you say and how you present things. You know, like I said...[their] innocence is gone....Their whole way of thinking is completely different over there. That just affects how they respond to you when they come home."

One of the limitations to verbatim theater is that it can only use the language that comes up in the interviews. If the interviewed veterans and wives avoid certain topics or perspectives, then the show must necessarily also avoid those topics. Verbatim theater holds a mirror up to nature, but cannot completely control the quality of the nature that enters its frame; just as the academic disciplines of ethnography and political theory often stress different dimensions of the same problems, so verbatim theater and 'regular' theater differ in their outcomes, though not necessarily in effectiveness. The use of multimedia and music helps BASETRACK LIVE overcome the limitations of verbatim theater, as these cinematic elements transform everyday language into poetry through the use of echo, repetition, and underlined sound. The band, which consists of the outstanding quartet of Trevor Extor, Kenneth Rodriguez, Mazz Swift, and Daniele Cavalca, elevates the play with relentless intensity--Schiller and Goethe would be pleased.

If there is room for refinement, it might lie in the combat scene. AJ, the lead character, remembers a sudden unleashing of 'chaos.' But an American infantrymen, when pressed, can reveal a precision to a combat that consists of casualty reports, air support, covering fire, and fire commands, the sum of which grants combat the frightening (yet empowering) quality of a testosterone and adrenaline riddled blood-sport. This 'precision' in midst of seeming 'chaos' helps explain the willingness of soldiers to return to the fire time and time again. American soldiers, backed with taxpayer equipment, feel that they can win any firefight they stumble into (more often than not). And so the combat scene could use further exploration (but not too much). In regards to content, the play might also consider pointing out that an American soldier's pay increases dramatically when stationed overseas, thus enabling the purchase of expensive Oakley's, new pickup trucks, new tattoos, and guns, guns, guns once a soldier returns home. There are a also a few moments of humor that may require a little more direction in order to cue the audience that laughter is acceptable in a war story.

But my complaints are mild, and my praise is strong. BASETRACK LIVE provides an intelligent, graceful way to empathize with the twenty-first century military experience. For a veteran like myself, it brought back surprising memories and shadows. It is a painful, sad place to go. The passages in which the soldiers contemplate suicide are particularly haunting, and open doors I prefer to keep locked and closed. But it is worth opening those doors to remind oneself that the war in Afghanistan, though perpetually 'winding down,' continues instead with perpetual cost. As it was in 2001, so it continued in 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, and 2014.

The BASETRACK LIVE project must continue. One hopes the creative team might consider asking the Afghans, who have now fought against (and alongside) the Americans for thirteen years, what they think of us. With the exception of Hamid Karzai, it often feels that we have thought painfully little of them. BASETRACK LIVE shows us a video in which an Afghan woman screams at the presence of a video camera in her family home; I walked away from BASETRACK without much of an understanding of her pain, but that seems fitting in a portrait that emphasizes the 1-8 Marines and the struggles they face within their own homes upon returning from combat. The play is now on tour. Seek it out.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed