The life of Edmund Allenby, a soldier and a statesman, in many ways anticipated the trials of his first biographer, Archibald Wavell. Born of "old-rooted English stock," Allenby grew into a tall, barrel-chested young cavalry officer. He served among the first generation of officers in which attendance at Staff College, rather than purchase, ensured promotion. He loved literature, the outdoors, and hunting; his letters to his wife rarely depict warfare, but often mention nature. Allenby's first experience in a contest of arms occurred during the Boer War of 1899-1902. He served ably, but more importantly he developed connections with the soldiers who later became the key officers of the First World War. Such connections helped ensure his promotion through the ranks. When the Great War began he immediately assumed command of a division of cavalry as a major-general. But the weight of command transformed his personality, so that an "easy-going young officer and a good-humoured squadron leader [became] a strict colonel, an irascible brigadier, and an explosive general." Out of fear and resentment, his men coined him "The Bull." The early years of the First World War cemented his reputation, as thousands of men died under Allenby's command as he bluntly executed orders from above. The year 1917 proved particularly fateful. Allenby began the year with serious losses at the Battle of Arrass, removal from the Western front, and the loss of his only son to German artillery shells; Allenby ended the year in the Middle East with the conquest of Jerusalem. The next year, he conquered Damascus. Given fresh resources and a weakened enemy, Allenby commanded one of the most decisive and efficient campaigns in the history of modern warfare as he swept up the Mediterranean coast and destroyed the Ottoman Empire. His relentless energy provided the Egyptian Expeditionary Force with the necessary momentum to decisively defeat the enemy.

T.E. Lawrence's Seven Pillars of Wisdom gives a far more heroic portrait of Allenby than Wavell does here; in fact, Wavell goes to great lengths to temper Lawrence's praise with a sober assessment of Allenby's flaws: his zeal for rules, loyalty, and unquestioned service. Wavell writes with praise, and yet a subtle sense of irony creeps into the biography, as though Wavell no longer believes in greatness. While it lacks the humor of some of Wavell's other works, the book sustains interest as a surprisingly impersonal reflection on Wavell's views of military and civilian leadership.

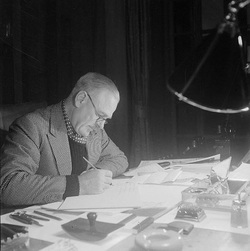

Archibald Wavell (Field Marshal, Viscount, and Viceroy of India) published his two volume biography of Field Marshall Edmund Allenby in the midst of his own challenges. Wavell served under Allenby in the First World War as a liaison and a staff officer with the Egyptian Expeditionary Force. As Wavell finished the first volume of the biography, he served as Commander in Chief in the Middle East, a status similar to the command Allenby once held. As Wavell finished the second volume, he held the Viceroyalty of India, a status somewhat greater than Allenby's eventual post of High Commissioner of Egypt and the Sudan.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed