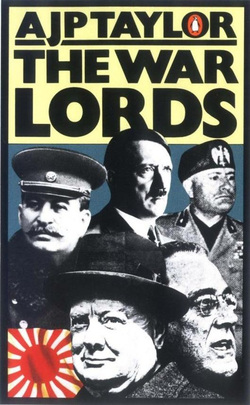

I am including this entry in my 'book review' series, but it differs in nature. Rather than judging A.J.P. Taylor's The War Lords as a history book, I merely attempt to capture his argument. I also try to emulate his clipped prose, when appropriate.

The War Lords stemmed from a lecture series that Taylor presented on the BBC. In the series, Taylor spoke completely off-the-cuff and without notes, as was his custom. For the book, he merely adapted and edited the type-written transcript of his lectures. The War Lords touches upon themes that Taylor explores with greater detail in other books; thus, readers familiar with A.J.P. Taylor will find much of the material redundant. But he also turns his gaze in directions that he otherwise ignored--especially at the power and personality of Franklin D. Roosevelt.

It seems impossible to connect Taylor's use of the term 'war lord' to any other era, even periods as recent as the First World War. Taylor himself states "In the First World War, curiously enough, there were no war lords." The only other war lords he names are Attila the Hun and Napoleon. The criteria remain unclear for the title 'war lord.' In Taylor's opinion, the five individuals under review arose from very particular circumstances. They share characteristics with the demagogues of Athens, for they each made exceptional use of boldness and public charisma to define a path up to and through the Second World War.

Taylor begins the book with a breathless preface that offers a window into his powers of analysis. A full quote better demonstrates the effect than any summary:

"Five of the lectures are biographical studies of the men who exercised supreme power during the Second World War; the sixth explains why there was no such man in Japan nor indeed any supreme direction at all. There is a deeper theme. Most wars in modern times have been run by a confusion of committees and rival authorities. The Second World War was uniquely different. In September 1939 the British and French governments declared war on Germany. Otherwise virtually every great decision of the Second World War was made by one of these five men except when the chaotic anarchy of Japan intervened. Each of the five was unmistakably a war lord, determining the fate of mankind. Yet each had an individual character and method that makes generalisation difficult.

"Three were avowedly dictators; two exercised their dictatorship with an outward respect for constitutional forms. One, Mussolini, was lazy. Three ran the operations of war from day to day, Stalin almost from hour to hour. Roosevelt observed the war with casual detachment until the moment for decision arrived. All had served in the First World War, though Roosevelt served only in a civilian office. Four were prolific writers; Roosevelt never wrote anything, not even his own speeches. Four were masters of the radio; only Stalin owed his power entirely to other means. Two were amateur painters; one was an amateur violinist. One was the grandson of a duke. One came from a rich professional family. One was the son of a customs official. Two were the sons of humble workers. Only one received a university education. One was happily married. One ran after every woman who came in sight. One was unhappily married. One was a widower. The fifth married only the day before he died.

"This was a bewildering variety. But the five had some things in common. Each of them dominated the service chiefs. Each determined his policy of his country. All five were set on victory, though of course not all could achieve it. They provided the springs of action throughout the years of war. This was an astonishing assertion of the Individual in what is often known as the age of the masses."

Taylor concentrates on the wartime decisions and personal characteristics of the major figures of the Second World War. He sketches rapidly, and without great detail. He adds a bit of background, and concentrates on the eyes--he wants to know where his 'war lords' are looking, and why.

Taylor argues more persuasively and more consistently in another of his popular history books, The Illustrated History of the Second World War. But here his task is entertainment, rather than serious learning. As with his Illustrated History series, Taylor fills the book with captioned photos that prove as informative as his text; yet here the photos are much more narrow in scope, for they center around his 'war lords.' And, despite the term 'war lord,' political leaders rarely engage in anything visually striking. For the most part, the leaders stand or sit in the company of mentors, peers, and ministers, and smile or grimace at the camera.

The photos of Mussolini make an exception--Taylor expertly captures the way the "Western world" saw Mussolini during the height of his power: the able sportsman and the every-man, the courageous warrior and the elite politician. And so we see how a man who looks like a clownish fraud in the present resembled a charming futurist in the past.

MUSSOLINI

Taylor begins the book with Mussolini. In a way, the entire era of the Second World War began with Mussolini's rise to power, for he initiated the conservative world's love affair with the illusions of a fascist modernity. Mussolini projected an image of constancy in a time of doubt and strife, yet a constancy perfectly in tune with ever-increasing wealth and power and technological advancement; the image appeared seductive enough that many individuals fell into the grip. He represented a self-confident alternative to socialism.

Like Hitler, Mussolini "served in the trenches--and the Italian trenches were perhaps the worst trenches in Europe, with the harshest conditions, where nothing was done for the ordinary men." The harshness of the trenches distilled his early socialist leanings into an entirely new form of politics--20th century fascism. He fed off of popular discontent. He organized ex-servicemen and formed task forces to resist the working-class socialist movements. Mussolini and his 'Black Shirt' party began to march throughout the country. When the army refused to intervene against Mussolini, the king of Italy made him prime minister. Mussolini's party concentrated power around him with tools of coercion, including murder.

While other countries felt buffeted from winds of distress and open political conflict, Italy projected an image of unity and modernity.

Mussolini built an image of Italy as a powerful military leader; the image proved far too successful for his own good. The shows of force deluded Mussolini, and led him astray. "As he looked at these masses of marching troops shown to him on the screen, he really believed that Italy had an army of five million. The actual figure was not much more than a million when it came to the point." He played the role of the every-man, he played the role of peace-maker (at Munich), and eventually he played the role of war lord. But in the role of war lord (as with the role of peace-maker) he could only play and project--he could not execute, nor achieve success.

He entered the war against Britain just before the collapse of France. He hoped for a share in German glory. But Britain failed to negotiate a peace, and instead won the Battle of Britain; unable to strike at Germany, Britain turned on Italy in both the Mediterranean and Africa. Thus Mussolini finally swung a sword he had shined for twenty years, only to find that it shattered when actually put to use against another European power. Such delusions are the cost of dictatorship; the dictator mitigates the risk of lost power, but maximizes the risk of bad information. When no one gains for creating their own interpretation of events, they quickly learn to keep their mouths shut.

The Italians began to look for a way out of the war, but the Germans did not allow Mussolini to capitulate at a reasonable hour. So Mussolini carried on as his power evaporated. Eventually, a partisan communist gunned him down. The partisans hung Mussolini upside down beside his mistress, Clara Petacci.

The image of the defeated Duce resonated strongly--even theatrically-- back in Britain. Laurence Olivier made use of it at the Old Vic to represent the conclusion of Shakespeare's Coriolanus, and Kevin Spacey recreated the image a few years ago for the conclusion of Richard III.

HITLER

A.J.P. Taylor interprets Adolf Hitler as an exceptional propagandist with the typical interests of a world leader: respect, security, and economic growth; Taylor's interpretation thus widely differs from the popular idea of Hitler as a madman and ruthless xenophobic, solely responsible for the ills of the Second World War. I am not interested in making a determination one way or the other, though I would say that his behavior--even his cruel xenophobia--fits well within the framework of human behavior during wartime, even if it sits outside of the Geneva convention. This does not make it morally excusable whatsoever. But it does suggest that 21st century moral conventions cannot help understand the psychological processes that governed his actions.

Hitler--like many Germans--despised the peace settlement that concluded the First World War. The economic depression and period of hyper-inflation afforded him the opportunity to rise to power on a wave of bourgeois discontent. Unable to effect a political revolt in 1923, he learned to pervert the constitutional process of the Weimar Republic and eventually assumed the chancellorship. He succeeded Hindenburg in the presidency, and also assumed the mantle of war minister in 1938, thus securing all the major positions of political power in Germany. He further consolidated power using the methods of Mussolini and Stalin though, in comparison with Stalin, he killed fewer people in the process (but left a far greater scar on the Western psyche).

Hitler's forces invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. This brought France and Britain into the war. He personally made the strategic decision to invade France, as he wanted to confront 'the greatest army in Europe' on his terms rather than theirs. He defeated them with unexpected swiftness, but then failed to completely defeat Britain.

Now Hitler faced a dilemma. He had an army, well-trained and tested, but no continental battles to fight. He lacked the naval power to seriously contest the British Isles. "By 1941, he was absolutely convinced that unless he struck a blow against Russian first and knocked the Russians out, they would, one day, when perhaps his conflict with Britain had got more acute, turn against him; they would betray him." But the strike at Russia did not appear desperate or paranoid at the time. Most expected Russia's quick capitulation. Perhaps they thought Stalin's tyranny left him atop a house of cards, much like Mussolini.

This proved the gravest strategic error of the war. Within the year, the German army halted within sight of Moscow. "This was the turning-point of the Second World War," Taylor averred. "In June 1941, Germany was the acknowledge victor, dominant over the whole of Europe. In December 1941, the German forces halted in front of Moscow. They were never to take it... and from that moment, Hitler appreciated that total victory could not be achieved."

Hitler appears never to have attempted a compromise peace--he never even seems to have entertained it. He found Japan's attack on the United States inspiring, and "for this and for no other reason, he plunged, at the end of 1941, the very time of his Moscow disasters, into the Japanese War."

As he declared war on America, "he made at this time the most extraordinary remark: 'We have chosen the wrong side; we ought to be the allies of the Anglo-Saxon powers. But providence has imposed on us this world-historical mistake.'" It should, perhaps, sober the self-righteous 'Anglo-Saxon powers' that Hitler felt more kinship with the United Kingdom and the United States than with any other nation; this was not delusional; he recognized the seeds of his own sources of power in these advanced industrial nations. Rising working-class discontent and xenophobia struck fear into the electorates of both the United Kingdom and the United States.

Hitler envisioned a collapse of the Soviet-British-American alliance. It never occurred. Their differing ideologies and regime-types did not result in open conflict. The more Hitler held together his own regime, the more the Allies had to lean together to destroy him. He became the centrifugal axis of the alliance.

The responsibility eventually broke him, and caused more damage than the assassination attempt that left him crippled. He weakened, physically and mentally. He indulged in fantasy.

Taylor places the 'inspiration' for the horrors of the Holocaust more on the shoulders of Himmler, rather than Hitler, "though Hitler took it up." Taylor does not explore Hitler's xenophobia any deeper than that.

Taylor ends his discussion of Hitler on a strange and sympathetic note. "With his death and disappearance, Hitler performed a final service to the German people--he carried with him into obscurity the responsibility for the world war and the guilt for the crimes and atrocities with which it had been accompanied. As a result, the German people were left innocent."

No other 'war lord' intervened more effectively in strategy, and with greater success. His initial successes left his generals and civilian ministers in a poor position to seize the reigns as Hitler's abilities broke down.

CHURCHILL

The war ruined the image of Mussolini; the war saved the image of Churchill. He served in high public office for most of the 20th century, and experienced war as a young soldier, a journalist, and a politician. In the First World War, Churchill's career nearly died on the shores of Gallipoli; he recovered, and towards the end of the war he followed in Lloyd George's footsteps as the Minister of Munitions, and then Secretary of State for War and Secretary of State for Air. In between the loss at Gallipoli and his return to power, he served briefly in the trenches as an artillery officer.

Taylor however skips much of this, and the interwar years, and instead begins in May, 1940, "after the unsuccessful British campaign in Norway--a campaign, ironically, for which Churchill was mainly responsible and the failures of which were due more to him than to Chamberlain, the prime minister who was actually discredited." Nevertheless, Churchill became prime minister.

Taylor remembers Churchill's assumption of the premiership as a contentious and uncertain moment; the confidence and glory only came in hindsight. But Churchill possessed gifts that suited him to the task. He could look back into history and draw useful lessons; he could look into the present and demand the most of modern technology. And he could put his ideas together coherently, even if some of those ideas deserved less attention than they received. Roosevelt once said of him, "Winston has a hundred ideas every day. One of them is bound to be right."

Perhaps most importantly, Churchill determined the direction of the conflict: it would go on, even after the fall of France in 1940. He ensured that the British Empire would not sue for peace, though the British could not defeat Germany on its own. Ultimately, Hitler was probably destined to lose the war to Stalin, but Churchill's insistence on continuing the fight ensured a prominent place for capitalist-democratic governance at the war's conclusion.

During the prosecution of the war, Churchill loathed open opposition. As a consequence he sacked Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, the victor of the Battle of Britain. He sacked Auchinleck. He sacked Wavell. Each general won major victories; each suffered relatively minor defeats, and often made do with minimal resources due to Churchill's incessant striving on ineffective campaigns. But a certain amount of 'sacking' proved useful, as generals tire during the course of a war; furthermore, a general well-suited to defense may prove incapable of forming an effective offense. So Churchill's habit of sacking generals on a regular basis proved a boon, rather than a burden, even if he acted unjustly to the individual officers involved.

After the Dunkirk evacuation of May-June 1940, a pall settled over the forests of northern Europe; the war shifted to the Mediterranean. "If you ask what the Mediterranean campaign was about, why the British were ever in the Mediterranean, one can give the simple answer of the Second World War, as of the First on some occasions: they were there because they were there--because they were there. And being there, then they had better stay there and fight." The British did not return to the continent until 1944. They had colonial and territorial holdings in the Middle East, and they had armies in place. They used these armies, for there was no other way to prosecute the war.

Churchill worked with relentless energy. He wore out those who could not keep up. He spoke with "a mixture of high rhetoric and humor. His speeches sound better now perhaps than they did at the time, when they did not always come across very well, though they were undoubtedly inspiring. The fact that he was always so lively also brought inspiration to others..."

"He made many mistakes. All war lords make mistakes. Churchill's mistakes were the mistakes of hurrying too much, of wanting victory too soon and wanting it with inadequate means... when he could not do something effective, he would do something ineffective... Nevertheless, on most of the great issues, though not on all, he was restrained."

Interestingly, the last great imperialist sacrificed much of the Britain's credit in the eastern empire to defend the Mediterranean. The fall of Singapore signified the end of Britain's ability to safeguard its colonial interests.

But on the other hand he did not hesitate to work with Stalin, despite having previously run the wars of intervention. He shared in the glory with the United States and the Soviet Union, and mitigated the shallow bickering that took place among the allies in the First World War.

"At a time when his physical powers were waning, Churchill still continued to survey the whole field of war, and even the most critical would hesitate to say that anyone could have taken his place... there was in Churchill, a combination of the profound strategist, the experienced man and the actor. Not always the tragic actor; there was a rich comedy about him as well. No other war leader, I think, had the same depth of personal fascination as Churchill... he combined, to the end, imperial greatness with human simplicity."

STALIN

"Most people, I suppose, regard Stalin as a monster." Yet at the time of the Bolshevik revolution he seemed 'a grey blur.' No one anticipated that he would become the most powerful leader of the Second World War, nor that he would have the greatest longevity in office.

He fought as a Bolshevik general in the wars of intervention; during that conflict, he ignored Trostky's instructions with an impunity that he never accepted from his own subordinates.

Stalin seized power after the death of Lenin. First, he attacked the enemies of his friends, and then he killed off the friends that disagreed with him, or that offered palatable alternatives to his own ruthless approach. "So in 1939, when the Second World War began, Stalin stood alone, puzzled, suspicious, with nobody whom he respected, nobody whose opinions he accepted, and hardly aware of the world outside the Soviet Union." Hitler and the British suspected Stalin's isolation would be his downfall. Stalin may have agreed with them to extent, for he did everything in his power to avoid war with Germany. Hitler invaded anyway. The Germans crossed the Russian frontier on 22 June 1941.

But Stalin overcame his isolation, and under his authority the Russians withstood the assault of up to four-fifths of the German army, and all of its best divisions.

Russia did not accomplish this easily. In the early days of the war, Stalin had under-performing generals shot under the auspices of a court martial. No other 'war lord' had his generals shot for failure in the field.

Stalin managed the war on three vast fronts, and remained absolutely involved in raising, equipping, and fielding his forces. He managed the war to an even greater degree than Hitler, who trusted an extensive professional staff.

Stalin's army failed to take advantage of its superiority in men and resources early in the war. He simply lacked the patience to withstand German offensives without immediately counter-attacking. He lost many of his forces due to his rashness. But at Stalingrad and Kursk he learned patience, and shattered the German armies as they exhausted their energy on his entrenched forces.

Taylor argues that Stalin did not seriously think of political conquest during the Second World War. His sole aim was to beat Hitler. In this way, he closely mirrored the mindset of Churchill: 'I have only one aim in life--that is to beat Hitler. This makes everything simple for me.'

The Soviets lost twenty million people in the war. "The Russians, and Stalin personally, were set on total defeat [of Germany], on exacting the unconditional surrender of the Germans, long before Roosevelt formulated this."

"A number of those who were at the conferences remarked on the fact that both Churchill and Roosevelt brought with them a whole host of advisers... [but] Stalin could do all the negotiating, he could discuss all the military problems, he could discuss all the political problems and had an absolutely tight grasp of them. Whatever he had been in earlier years, he grew up into being a statesman; one who, without doubt, was totally devoted to the interests of his own country, but also of very great gifts and, in some ways, of considerable sentiment and responsiveness."

He possessed a savage sense of humor. He joked about shooting diplomats, generals, and friends; it's hard to see the humor in this, especially since he really did shoot diplomats, generals and friends. But still, he had, like the other leaders of the Second World War, a sense of humor.

"Stalin I think, assumed, as so many people do, that the relations based on war would go on when the war was over: that there will be the same feeling of 'Well, we must agree because we're allies in a great war.' But, of course, what happened is that, when the war was over there was no longer the same intensity of need to agree. And Stalin was very quick to respond suspiciously."

"We know comparatively little about his last years. He became increasingly suspicious and the gifts and brilliance which he had shown appeared to vanish. Indeed, many people think, in the end, he became mad with suspicion, and was proposing a vast new liquidation.

"When he died, he was treated as one of the greatest heroes Soviet Russia had ever known, but thereafter he was lowered and degraded. At first, his remains were placed beside those of Lenin; nowadays, though, they have a more modest position under the Kremlin wall.

"The last word, perhaps, goes to Averell Harriman, who was American ambassador to Moscow during the Second World War. He found Stalin better informed than Roosevelt, more realistic than Churchill--perhaps the most effective of the war lords."

ROOSEVELT

A.J.P. Taylor distrusts Roosevelt; had Taylor written more on him, we might have learned that Taylor distrusts the American Presidency as an institution. Americans hold their presidents accountable for perceived economic performance. Interestingly, presidents have little control over the economy. So the sort of person who assumes the office--weirdly--posses incredible powers over the conduct of warfare, but little over that with which he most concerns himself, namely the economy. The individuals who occupy the office look distinct (and odd) when contrasted with totalitarian or parliamentarian leaders.

Unlike the other 'war lords' of the Second World War, Franklin Delano Roosevelt did not see uniformed military service during the First World War. Instead, he held a political post, the assistant secrataryship of the American navy.

"Roosevelt was also the odd man out in another way; he was totally political. If you look at the others, you will see that they had other interests. All of them wrote books, though of different kinds. Roosevelt never wrote anything, except rather casual private letters... However, some of the finest phrases [of his speeches], such as 'the only thing we have to fear is fear itself,' were inserted by Roosevelt at the last moment."

"His background did not prepare him at all to be a war lord," Taylor wrote. He came to power facing 'perhaps the worst crisis that any modern country has ever faced" though America was perhaps uniquely suited to overcoming the Great Depression, with its vast natural resources, potential for advanced industrialization, cheap labor, and population growth.

"Roosevelt had no preconceived ideas about economics or, for that matter, about war... I am tempted to say that he had no principles. I do not mean by that that he was wicked, but that he operated only in response to a situation, and decided only at the very last minute." In that way he fundamentally differed from Woodrow Wilson, the American president that entered the First World War, and idealistically sought to end all wars altogether. Roosevelt did have hopes, however, and those hopes centered around economic prosperity and the American economic system. And though the American economy performed well during the war, it worked best during times of peace. So he looked forward to the construction of the United Nations as an "essential way forward for mankind, and that it would work." In other words, that it could prevent another world war. And the United Nations certainly proved a useful instrument for keeping the Cold War from getting any hotter than it did.

Roosevelt let the war come to him. Though some of his opponents and naysayers look for conspiratorial evidence that he sought to drag the U.S. into the war, this seems not only absurd but contrary to his character. He waited for situations to develop and chose political solutions to economic, moral, and social situations. Of the 'war lords,' he most carefully managed his country's economic prowess. While the other nations bent their economic power solely towards the immediate conflict, the United States profited tremendously from the war. "Although the Americans supplied the weapons of war, they also squeezed Great Britain dry economically; and that was Roosevelt's deliberate policy."

Roosevelt did not place Great Britain unequivocally on the side of good. He (and many other Americans) distrusted European imperialism intensely.

Roosevelt imposed an economic embargo on Japan, which Taylor refers to as "a delayed declaration of war." Yet if it was a declaration of war, the United States made little effort to anticipate any attack. And prior to 7 December 1941, a series of absurd bureaucratic military blunders in Washington led to complete surprise during the attack at Pearl Harbor. Both Admiral Stark and General Marshall failed to act efficiently when intelligence officers relayed fears of an impending assault.

Before America ever engaged in actual combat operations, the embargo began strangling the Japanese economy, while the lend-lease program upheld the British economy. War was clearly on the way. "Pearl Harbor solved Roosevelt's problem, for he would have had great difficulty bringing the American people in to the war if it had not been for the Japanese attack on it and the German ultimatum that followed... From that time, Roosevelt was commander-in-chief of the American armed forces in practice as well as in theory." In other words, he did not involve himself in military affairs until the war actually began; he became a 'war lord,' but he was not a warmonger. In this way he differed significantly from Hitler and Mussolini, Churchill and Stalin.

Upon entering the war, Roosevelt made a number of decisive, non-obvious choices. First, he determined to defeat Germany before going after Japan. Second, he sent the American army to fight in North Africa and Italy prior opening a second front in continental Europe. He wanted to start fighting immediately (or at least as soon as possible), but the invasion of Europe required a greater build-up of arms than the Americans could manage in 1942. Taylor cynically states that Americans fighting in battle (or at least clearly on the way to fighting in a battle) would help ensure victory in the 1942 congressional elections; Taylor is probably right.

When it came to strategy, Roosevelt took an economic approach, both simple and wise: he felt that the way to win a modern war was to have absolutely more of everything than your opponent. And though it took awhile to get going, eventually he did.

"By 1944, Great Britain had become much overshadowed by this American power, which Roosevelt had developed by always setting the targets higher than any American industrialist thought would be possible, and these being achieved."

Roosevelt worked hard to establish and maintain a close working relationship with the allies. Unlike many Americans, he did not regard the Russians as totally divided from them by a barrier of principle. "Relations between West and East were warmer in Roosevelt's time, not because, as people say, he made unreasonable concessions, but because he was the only Western statesman of that period who really treated the Soviet Union as an equal." This represented a wise political move, for the Soviet Union possessed far more raw military power than any other country during the Second World War. But Roosevelt did not realize this at the time; rather, his political approach to diplomacy simply rested on the assumed courtesy of equal treatment; for the same reason, the Chinese dictator Chiang Kai-Shek received far more serious attention from Roosevelt than Churchill or Stalin.

Roosevelt set the United States on track for becoming the greatest power of the 20th century, for he found a sustainable path towards maintaining a balance of economic and military might. Counting soldiers represents a reasonable way of assessing military strength during a battle, but the easy (and unburdeonsome) buttressing of those soldiers over a period of many years signals the country's strength in the long run. And Roosevelt established a precedent for balancing economic development and military power such that the maintenance of his military arms never sank his country into an endless pool of debt, nor crippled its industry with centralized micromanagement.

JAPAN: WAR LORDS ANONYMOUS

"The Japanese have some claim, I suppose, to the original war lords. Their country, for some hundreds of years, was under the control of war lords--the samurai. And yet, in the Second World War, the Japanese diverged entirely from the pattern which I have been presenting in previous lectures: there was no Japanese war lord--no single figure who led Japan into war, who directed the war, who made the decisions, and so on."

Tojo is often mistaken for a war lord. But in Taylor's view he merely represented a wide class of generals and admirals and politicians who contributed towards Japanese policy-making.

The Japanese withdrew from the world until forced open by American gunboats in 1867. Within an astonishingly short period of time, they adopted 'all the lessons of Europe' on constitutionalism, industrialism, and parliamentarianism. They elevated their religious figure, the emperor, into the position of head of state. They adopted modern military practices. "Modern Japan grew out of European history, and the Japanese view was that if they loyally, carefully, pedantically followed the European patterns, they would be transformed into an acceptable member of the great power family." In the early 20th century, Japan fought against the Russians and emerged victorious. In the First World War, they joined the allied cause, and suggested that the League of Nations adopt a clause laying down racial equality as a principle; they assumed it would be accepted.

But it was defeated by none other than President Wilson. And then the Americans placed a total ban on the migration of Japanese into the United States. "The Japanese learnt a lesson: the rules which applied to white men did not apply to what Churchill used to call 'those funny little yellow folk.' Racial equality was far from being achieved. This, among other things, no doubt made the Japanese more sensitive and more aggressive."

Japans political structure bore some unique characteristics. To prevent the emperor from the embarrassment of ever being wrong, the ministers and generals had to arrive at complete consensus before presenting a matter for his opinion. In the face of absolute consensus and zero information, the emperor could only nod his head and agree with the supposedly obvious course of action. Just as crucially, military leaders were responsible for making all military decisions--not just of strategy, but of overall action. And the Japanese established the convention of an 'autonomous supreme command,' so that military leaders worked entirely independently of civilian leaders subsequent an initial engagement. Once the country stepped on the accelerator and towards war, they effectively cut the brakes.

Officers both young and old wanted Japan recognized as a great power. Patriotism fueled this desire. And war seemed the way forward. So when any minister seemed incapable of pushing the country further towards greatness, an individual took it upon themselves to assassinate that minister. The internal political violence of Japan thus differed greatly from the more centralized party violence of Nazi Germany. "In a short space of time, two prime ministers were assassinated, one after the other, [and] also a number of generals and leading officers. From then on, all those who followed a cautious, sane policy did so with great stealth. If they appeared to be too cautious, they would be certain to be assassinated. Not that the Japanese ministers and officers feared assassination in itself; it was that their assassination made their policies ineffective. Therefore, far from the leaders conspiring to bring about war... they conspired to bring about peace or, at any rate, to slow things down."

The greatest impulse for a Japanese war of conquest stemmed from Great Depression. The Japanese had embraced free trade. But at the onset of the Great Depression the United States and Great Britain raised enormous tariffs; while the Anglo powers maintained a lock on their own overseas holdings, Japan faced a strangle-hold. They turned to the rest of the Far East, most of which fell under a disorganized Chinese federalist state. They encouraged revolt in one part of China, and invaded in another. This received international rebuke, but no action.

The tension increased dramatically with the fall of France and the heavy fighting over the skies in Britain. Both Japan and the United States thought they might avert war by ratcheting up the tension even further, and thus threatening their Pacific rival into relative silence.

The United States placed an oil embargo on Japan in 1941. Japan had no oil of its own. "It was clear to the Japanese that, within not more than 19 months, Japanese oil would run out and Japan would collapse as a great power."

And so they attacked Pearl Harbor, seized the Pacific islands, annihilated British resistance in Singapore and slashed through Burma.

They did not expect American and British capitulation, but rather hoped America would tire and agree to a compromise solution. This did not occur.

"The Japanese owed their ultimate defeat to two things. One was the incredible economic strength of the United States, which enabled it, by 1943, to conduct both the war in Europe and the war in the Pacific. Against all Japanese calculations, the Americans were clearing up both at the same time. The other thing which led to Japan's defeat was its terrible mistake of neglecting to provide itself with anti-submarine devices. By 1943, Japans mercantile marine had lost three-quarters of its strength... By the beginning of 1945, most of the Japanese civilians and some of the more cautious generals recognised that the war was lost."

With the dropping of the first atomic bomb, the emperor finally intervened. He said: 'We have resolved to endure the unendurable and suffer what is insufferable." Shortly after he made the decision, the Americans dropped the second atomic bomb on Nagasaki.

MacArthur accepted Japan's unconditional surrender on 2 September 1945. The subsequent war tribunals spared the emperor of charges, but hung most of the high command, including Tojo.

So ended the Second World War.

* * * * * *

A brief assessment:

While The War Lords lacks the incisive insight of A.J.P. Taylor's other books, it still suggests an interesting and thought provoking argument: Each of the 'war lords' of the Second World War wielded vast powers with surprising autonomy vis a vis the leaders involved in other major conflicts in the 20th century; yet despite this similarity, each of the war lords came to power in remarkably different ways. Two fascists, a totalitarian socialist, a parliamentarian, and a president all conducted the Second World War with autonomy and independence.

Taylor does not probe into the causes of these similarities. He simply acknowledges them. He also makes little effort to demonstrate the autonomy of each of the 'war lords,' though he does the show the steps which prevented the emergence of a war lord in Japan.

Did the war lords truly act with autonomy during the Second World War? Why were they able to act freely without reference to constituents? In other words, was the brief era of autonomous war lords just a mirage?

One can imagine, for example, that because each of the leaders rose to power with a commitment to non-negotiable peace, they therefore had to sustain a commitment to war to prevent their hitherto allies and henchmen from turning on them. That would seem like a powerful constraint on behavior. Yet it remains plausible that someone like Churchill or Hitler simply refuses to acknowledge the plausibility of compromise. In such a situation, their own mind offers the greatest constraint upon their actions.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed