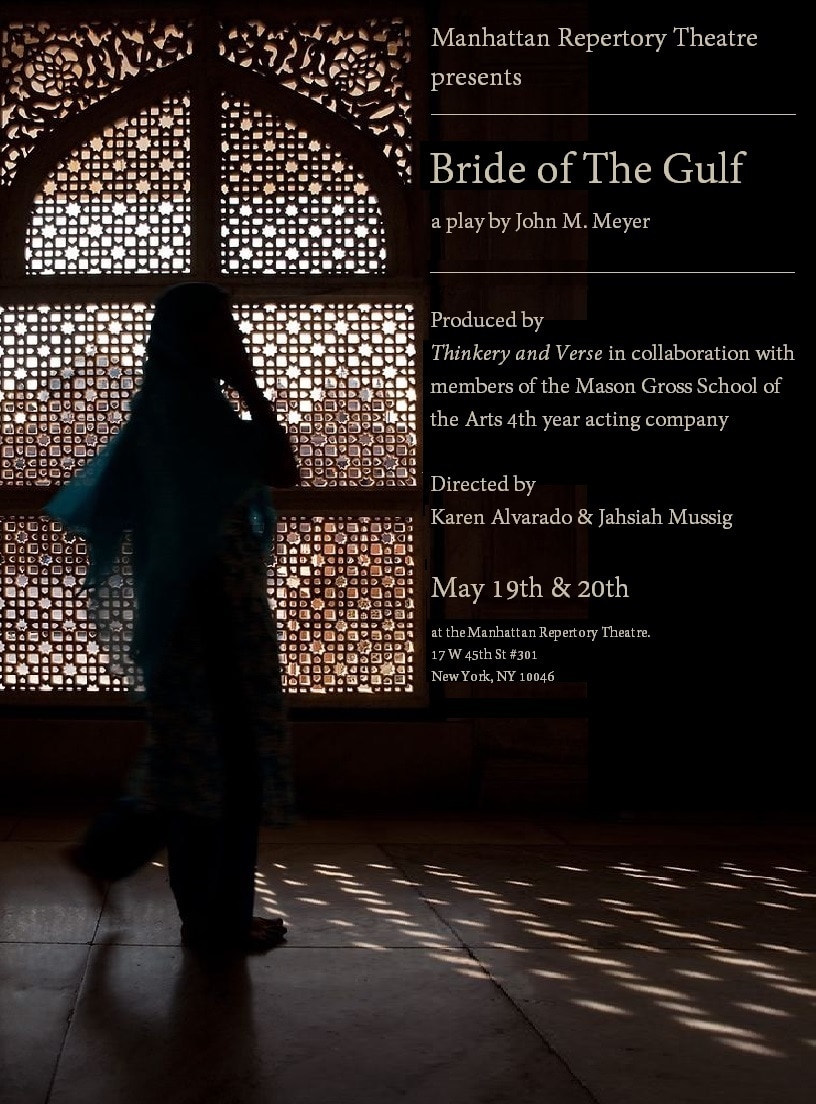

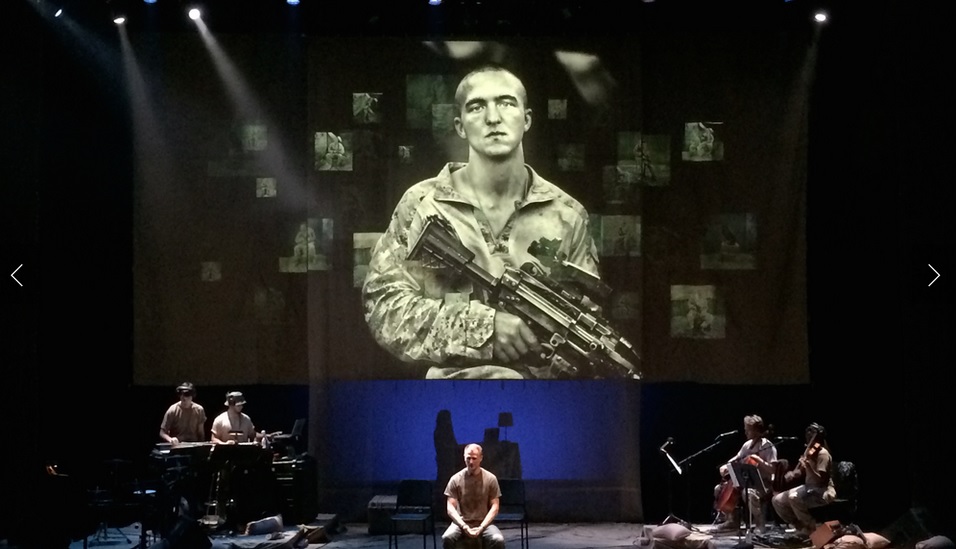

Bride of the Gulf is a new play that tackles the normality of war in Basra, Iraq through the deep, yet hostile relationship between a widow and her mother-in-law. Set amid the violence that engulfed Southern Iraq after the British withdrawal of 2007, a sharp-witted Iraqi woman goes in search of her missing husband at the behest of her mother-in-law. When creating the play for the Basra to Boston project, we drew on transnational conversations that took place throughout 2016, as well as the playwright's memories of Iraq in 2007.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed