But I'm largely clueless. I was asked to attend the mid-term review because of my dual backgrounds in theater and the military. The students in the class seek to design a 'space for veterans,' that includes a few studios and theaters for artistic expression.

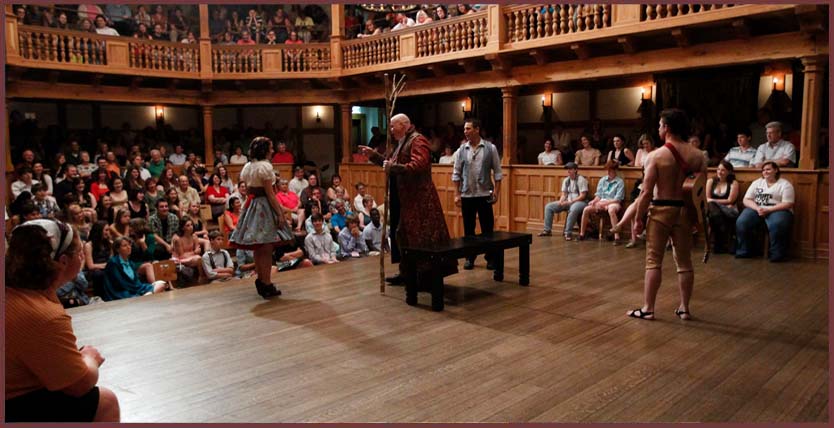

A few weeks ago, the same class asked me to describe a few of my favorite spaces. I told them that I expected to loathe the museum-minded efforts to rebuild the playhouses of Tudor and Stuart England, but that the performances that I experienced at the London's Globe and Staunton's Blackfriars checked my instincts. Instead, I found these playhouses remarkably alive. The audience-actor connections forced players on both sides of the stage to actively participate in bringing about the theatrical event. The effect, in fact, was even more pronounced in these spaces than in any other situation of universal lighting. Why?

And so when surveying the student projects, I looked for theater spaces that challenged the audience in the first instance, even before the start of a performance. I looked for spaces that I would want to wander through, even if no performances are going on. Meditative spaces. Spaces that wait for words, but that are not afraid to speak back. Spaces that are not a black box, but a box built for play within a wider and unalterable world.

Should a theatre space honor veterans? Perhaps. More importantly, it should honor our shared humanity. If theatre does something good for veterans, it rekindles a sense of play, a sense of imagination. It wakes a dormant fearlessness of making friends and companions, and building a new sense of community and public sharing.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed