My review of James Lang's On Course emphasized the practical attributes of successful teaching. My review of Mark Edmundson's Why Teach? examined current trends in academic life, and pleads for a more spiritually challenging curriculum. On Course uses some references to empirical data and peer-reviewed studies, but seeks mainly to provide firm guidance to young educators. Why Teach? eschews peer review to trace one intellectual's Walden-like musings on the modern intellectual wilderness. My sympathies lay with Edmundson, but my need for practical guidance brought me closer to Lang.

As luck would have it, this week's issue of Science included an article on education research. As with most articles in Science, the purpose of the piece is to establish what exactly a particular field can and cannot say based on the data available, and then to suggest new avenues of research. When it comes to human learning, these researchers find the entire field a chaotic mess. The authors attempt to build a few categorical fences to clarify things for both researchers and educators, but also use a little math to show the complexity of the issue.

Here is the math they use to demonstrate complexity. "If we consider just 15 of the 30 instructional techniques we identified, three alternative dosage levels, and the possibility of different dosage choices for early and late instruction, we compute 3^(15*2) or 205 trillion options... the vast size of this space reveals that simple two-sided debates about improving learning--in the scientific literature, as well as in the public forum--obscure the complexity that a productive science of instruction must address" (936).

In other words, the potential for research is almost overwhelmingly vast, and conducting it might prove overwhelmingly expensive. To encourage research rather than surrender, the authors suggest a framework within which future studies might operate. You can read their article if you wish to fully understand their suggestions, but I will briefly examine one aspect of their paper.

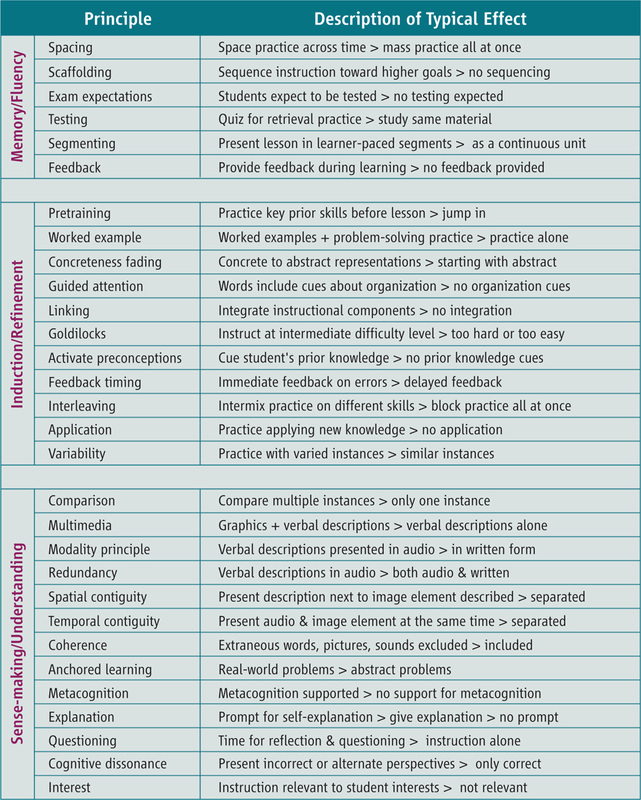

The authors produced a helpful table that reviews some of the current findings on 'instruction.' Much of the table draws on Koedinger, Corbett, and Perfetti's learning-to-instruction theoretical framework. Below, the authors of the Science article fit thirty nifty principles within three categories the authors call 'the functions of instruction' (936).

Some books should be articles, and some articles should be books. The lead author, Koedinger, has published extensively in his particular field (he earned an MS in Computer Science and PhD in Cognitive Science), but has not written a book on the subject. A book could include practical examples of his work, and show how he stumbles into and out of research problems. It would also give him the room to demonstrate that his research is useful to educators, as opposed to researchers that scientifically examine education. It is common scientific practice to laconically claim one's work has 'policy implications,' and yet have absolutely no significant evidence of one's ability to implicate, change, or effectively argue policy. Scientists should perhaps engage in politics more often than they do.

God knows I probably could have benefited from some of Professor Koedinger's knowledge when I myself haltingly studied geometry. "To the field, Koedinger, to the field."

*****

Clearly, we are far from 'perfecting' college instruction. Human limitations represent a permanent obstacle to ideal outcomes. In the face of those limitation, it is sometimes helpful to step back and use qualitative empirical studies to think through the purpose and effectiveness of college education. In this vein, the books of Ken Bain (president of the Best Teachers Institute) are helpful. Bain wrote a book entitled What the Best College Teachers Do (2004), and another called What the Best College Students Do (2012). The former book reported the findings of a fifteen year study that followed the habits and practices of some of the most successful educators in the United States. Not all together surprisingly, he found that the best instructors combined a deep knowledge of their subject with a belief in student learning. These two principles seem easy, but they are not easy to accomplish. Many (most?) teachers are out of touch with the most challenging questions in their discipline, and many others lack sympathy for the importance of undergraduate education.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed