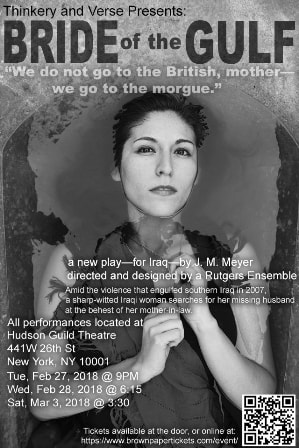

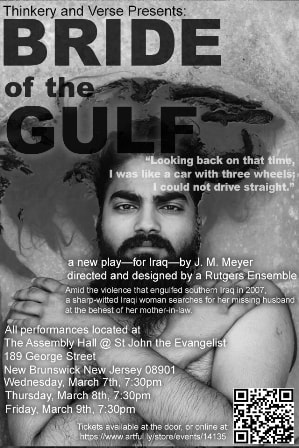

| Bride of the Gulf will preview for a limited run of six performances in New York and New Jersey in the spring of 2018. The first three shows will occur in Manhattan on: Tuesday, February 27th, 9pm Wednesday, February 28th, 6:15pm Saturday, March 3rd, 3:30pm These three performances will be a part of Winterfest @ Hudson Guild Theatre, 441W 26th St, New York, NY 10001. The play will then preview in New Brunswick, New Jersey at the Assembly Hall of St. John the Evangelist, 189 George Street, New Brunswick, New Jersey. The New Brunswick shows will occur on: Wednesday, March 7th, 7:30pm Thursday, March 8th, 7:30pm Friday, March 9th, 7:30pm Tickets are now available through Artful.ly ticketing services. In August 2018, Thinker & Verse plans to bring "Bride of the Gulf" to the Edinburgh Fringe for its international debut. |

|

0 Comments

I am pleased to say that a peer-reviewed article I wrote for the Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth Studies has just been published online. The print version should come out in a few months. Until then, here is the publisher's online link at Taylor & Francis.

Here is the abstract: "This article argues for the importance of the Royal Indian Navy mutiny of 1946 in two key aspects of the transition towards Indian independence: civilian control over the Indian military, and a competition for power between Congress and communists that undermined Indian workers and their student allies. "The article begins with an investigation of the mutiny drawing on three sources: a first-person account from a lead mutineer, a communist history of the mutiny, and the papers published in the Towards Freedom collection. "In 1946 a handful of low-ranking sailors sparked a naval mutiny that ultimately involved upwards of 20,000 sailors, and then crashed into the streets of Bombay with revolutionary fervour. The Communist Party in Bombay seized upon the mutiny as an opportunity to rally the working class against the British raj, with the hope of ending British rule through revolution rather than negotiation. "Yet the mutiny proved less of a harbinger of what was ending and more of a bellwether for what was to come. Congress, sensing the danger of the moment, snuffed out support for the mutiny, and insisted on a negotiated transfer of power. Congress’s action thereby set a precedent for civilian dominance over the military in postindependence India. At the same time, however, Congress betrayed the effectiveness of some of organised labour’s strongest advocates, namely the Communist Party, Bombay students and Bombay labour, thereby undermining their costly mass protest, and hobbling them in future conflicts against Indian capitalists." While my author's agreement does not allow me to place the polished, published version of the article on this website just yet, I am able to provide readers with the rough draft of the article I submitted to the editors. Here is the link to the rough draft: http://jmmeyer.weebly.com/royal_indian_navy_mutiny_1946.html If you would like to read the published version, simply contact me and I can e-mail it directly to you. Wavell, Archibald. Allenby: A Study in Greatness, George G. Harrap & Co. (Vol. 1 1940; Vol. II 1943.)

The life of Edmund Allenby, a soldier and a statesman, in many ways anticipated the trials of his first biographer, Archibald Wavell. Born of "old-rooted English stock," Allenby grew into a tall, barrel-chested young cavalry officer. He served among the first generation of officers in which attendance at Staff College, rather than purchase, ensured promotion. He loved literature, the outdoors, and hunting; his letters to his wife rarely depict warfare, but often mention nature. Allenby's first experience in a contest of arms occurred during the Boer War of 1899-1902. He served ably, but more importantly he developed connections with the soldiers who later became the key officers of the First World War. Such connections helped ensure his promotion through the ranks. When the Great War began he immediately assumed command of a division of cavalry as a major-general. But the weight of command transformed his personality, so that an "easy-going young officer and a good-humoured squadron leader [became] a strict colonel, an irascible brigadier, and an explosive general." Out of fear and resentment, his men coined him "The Bull." The early years of the First World War cemented his reputation, as thousands of men died under Allenby's command as he bluntly executed orders from above. The year 1917 proved particularly fateful. Allenby began the year with serious losses at the Battle of Arrass, removal from the Western front, and the loss of his only son to German artillery shells; Allenby ended the year in the Middle East with the conquest of Jerusalem. The next year, he conquered Damascus. Given fresh resources and a weakened enemy, Allenby commanded one of the most decisive and efficient campaigns in the history of modern warfare as he swept up the Mediterranean coast and destroyed the Ottoman Empire. His relentless energy provided the Egyptian Expeditionary Force with the necessary momentum to decisively defeat the enemy. T.E. Lawrence's Seven Pillars of Wisdom gives a far more heroic portrait of Allenby than Wavell does here; in fact, Wavell goes to great lengths to temper Lawrence's praise with a sober assessment of Allenby's flaws: his zeal for rules, loyalty, and unquestioned service. Wavell writes with praise, and yet a subtle sense of irony creeps into the biography, as though Wavell no longer believes in greatness. While it lacks the humor of some of Wavell's other works, the book sustains interest as a surprisingly impersonal reflection on Wavell's views of military and civilian leadership. Archibald Wavell (Field Marshal, Viscount, and Viceroy of India) published his two volume biography of Field Marshall Edmund Allenby in the midst of his own challenges. Wavell served under Allenby in the First World War as a liaison and a staff officer with the Egyptian Expeditionary Force. As Wavell finished the first volume of the biography, he served as Commander in Chief in the Middle East, a status similar to the command Allenby once held. As Wavell finished the second volume, he held the Viceroyalty of India, a status somewhat greater than Allenby's eventual post of High Commissioner of Egypt and the Sudan. Ever since Basil Liddel Hart's glowing statements on T.E. Lawrence strategic genius, Lawrence's reputation has centered on his military accomplishments, rather than his achievements in art. This is a mistake. Orde Wingate despised Lawrence's record as a war-leader, possibly because Wingate recognized something of his own failings in Lawrence. But Wingate also felt that Lawrence abdicated his personal responsibilities as an officer to play too much the desert warrior. There are no records of Wingate actually shooting an enemy in combat--he was too busy maintaining his supply line and keeping his troops on the march. Lawrence fired his weapon often, and preferred the emotional rush of battle to the more mundane tasks typically required of officers in combat. Lawrence's emphasis on action, in Wingate's view, was an abdication of responsibility. Lawrence's campaigns are often held up as a positive example of irregular warfare, and as a better way of fighting than what soldiers faced in the trenches of the First World War. Lawrence himself was not so sure that he was actually preserving life, or winning battles more efficiently. The numbers, in fact, indicate that he lost men at a higher rate than most British units that faced action on the Western front. This is not surprising. State control and industrial efficiency seems to reduce casualties, either because men lose their willingness to die as a mere part of a 'machine' rather than as an individual warrior, or else because industrial society provides soldiers with better access to medicine and stable rations. State control also increases the number of prisoners taken, and reduces the number of prisoners slaughtered. British methods of warfare and 'state control' might outright reduce the 'proportion' of people who die violently. Lawrence noticed this, which explains why he heaps praise upon Allenby above and beyond any other soldier in the First World War, and why he denigrates Allenby's rival commanders not as butchers, but as unimaginative sticks-in-the-mud. So why does Lawrence seem attracted to desert warfare? His writings indicate that he appreciated the straightforward human practicality of 'desert' warfare. Yes, the violence in the desert was terrible, but it was coupled with a familiarity, a spirit of adventure, and a sense of honor that Lawrence never felt while working for the British military in Cairo prior to his desert campaigns. The Arab 'irregulars' that fought beside Lawrence risked hearth and home in an immediate way. More than one of Lawrence's fighters, in fact, saw their homes destroyed by the Turks in retaliation for joining with the Arab revolt. More than one Arab also saw his village destroyed, and his family annihilated, during the panicked Turkish retreats from Palestine and western Jordan. And so the Arabs often risked not only their lives, but their families and tribes to fight the Turks--and sometimes each other. The Arab revolt involved a type of warfare that was less organized in the sense of mass bureaucracy and written protocol, and yet no less sophisticated in its nuance and complexity. And so Lawrence wrestles with the following, implicit idea throughout Seven Pillars of Wisdom: He senses that the Arab way of war is more virtuous, honorable, and personally fulfilling than the sort of violence that destroyed the lives of his friends and brothers along the European Western Front. But given that Lawrence knows the superiority of British warfare for battlefield outcomes (Lawrence always suspects the British will emerge triumphant), is it morally acceptable for him to dabble in Arab nationalism and 'desert warfare'? Lawrence believes that Arabia, Syria, and Mesopotamia rightfully belong to the Arabs--but he is a student of history, and knows that even as he props up a certain brand of Arab nationalism, he is setting in motion a thousand difficulties for hundreds of extant ethnic and religious groups living in the same region. Throughout Seven Pillars Lawrence examines his conscience, and recognizes that ultimately he has fought this war to satisfy his own peculiar appetite for violence, warfare, and chivalry. Many of his Arab friends admire him for it, but he considers himself a sham. The Arab irregulars, in Lawrence's eyes, live with the virtues of the desert; but he, their leader, merely wears the costume--he possesses the heart, but not the mind. The Arabs who followed Lawrence died at tremendous rates--nearly sixty of Lawrence's two-hundred personal bodyguards perished within a year. Their villages burned. Their children and wives lived unprotected, and hungry. The European powers, on the other hand, featured stronger, centralized state governments compared with Arabia, Mesopotamia, and Syria-Palestine. Even on the Western and Eastern fronts, preserved a macabre sense of decorum. Yes, terrible acts took place in the First World War--murder, rape, pillaging, poison gas and vicious trench fighting. But even then, the war in Europe obeyed strange rules: the taking of prisoners, the feeding of troops, and the separation between the war-front and the home-front. I conclude this letter with a couple of quotes from General Archibald Wavell, a man who fought alongside Lawrence in the Palestine campaign. "Lawrence had many fairy godmothers at his cradle, with gifts of fearlessness, of understanding, of a love of learning, of craftsmanship, of humour, of Spartan endurance, of frugality, of selflessness. But at last came the uninvited bad fairy to spoil his enjoyment...[she left him] with the gift of self-consciousness." That is to say, Lawrence was too aware of who he was, and who he was not. He was British, and a bastard-born, and not of Arabia. His education positively dripped with the soaking benefits wrought from state-sanctioned security and comfort. But he fought alongside his friends as though he were an Arab prince. He never forgave himself. He loathed the Turks, and often justified his actions in the war as a chance to destroy something he loathed. In this light, Wavell viewed Lawrence as "a Hamlet who had slain his uncle neatly and efficiently at the beginning of Act II, and spent the remainder of the play in repenting his act and writing a long explanation of it to Horatio." (Wavell The Good Soldier, 1948, 59-61). Lawrence of Arabia versus Seven Pillars of Wisdom David Lean's film, Lawrence of Arabia was a wild act of filmmaking. In today's terms it costs very little money, but it took the lavish resources of time and energy and passion. I want to quote a film critic, the late, great Roger Ebert on this film: "What a bold, mad act of genius it was, to make “Lawrence of Arabia,” or even think that it could be made. In the words years later of one of its stars, Omar Sharif: “If you are the man with the money and somebody comes to you and says he wants to make a film that's four hours long, with no stars, and no women, and no love story, and not much action either, and he wants to spend a huge amount of money to go film it in the desert--what would you say?” I think most people would say 'no.' Just like most people would refuse to follow Lawrence into Syria in 1911, before the war, much less in 1916, when the Arab revolt faced destruction along the shores of the Red Sea. But the people in our lives almost always say 'no.' That is what makes leadership, and art, and astonishing success so very rare. People say 'no,' because they are weak, and saying 'no' is easy. And yet, people said 'yes' to making 'Lawrence of Arabia.' Perhaps it was perhaps, the sort of British thing to do, as when Lionel de Rothschild loaned Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli the money to purchase the Egyptian shares of the Suez Canal. To return to Roger Ebert: "The impulse to make this movie was based, above all, on imagination. The story of “Lawrence” is not founded on violent battle scenes or cheap melodrama, but on David Lean's ability to imagine what it would look like to see...a speck appear...on the horizon of the desert, and slowly grow into a human being...He had to know how that would feel before he could convince himself that the project had a chance of being successful." Lean's film ultimately cost fifteen million, a fortune at the time, and it required Peter O'Toole to "stay in character" for almost two years of filming.

Lean rejected the original draft of the script, written by Michael Wilson, because it emphasized historical detail and political context. Lean wanted a portrait of human soul in a moment of crisis and exaltation, not a history lesson. Something must be said of the use of an Italian actor, a British actor and an Egyptian actor to play three of the key Arab roles. On the one hand it dangerously reminds us of the use of makeup to present stereotypes of other ethnic cultures. On the other hand, the actors, went to great lengths in their portrayals, going so far as to meeting with either their real life counterparts, or their descendants. Further, twenty-first century Hollywood would probably not insist on genuine, racially appropriate casting--but instead I suspect modern Hollywood simply would not fund the film whatsoever. I invite you all to talk about this more at another time. T.E. Lawrence's Seven Pillars of Wisdom rates as one of the greatest war memoirs of the 20th century. In its original published form, the memoir is filled with scores of full color portraits and wildly evocative abstract dreams that parallel the flights of fancy taken in the writing. It is a work of spiritual crisis measured through the changes of a millennium, rather than a single century. From that epic story, David Lean carved out what is often regarded as one of the top ten films of all time. The two works are almost not recognizable side by side. The film, which is easier to comprehend, obscures Seven Pillars of Wisdom, which is dense, and usually badly printed. It is an epic film, not because of its cost or its sets, but because Lawrence's character arc is as strong and as visible as a Roman arch. Lawrence's book devours a mythic feast among the bloodshed of the First World War, but Lean's film exists outside of the First World War altogether. They are two wholly different modes of art. Both are wonderful. Neither is a lesson for strategists. After his death, onlookers referred to Orde Wingate as a religious fanatic, an original thinker, and as a ruthless killer. Many of these charges stem from Wingate's time as the leader of the Special Night Squads. In 1938, in British Palestine, Wingate founded Jewish-British units called Special Night Squads; these units are now considered the forerunners of the modern Israeli Defense Forces. Many Israeli leaders, like Moshe Dayan, credited Wingate for inspiring Zionist leaders to adopt a more aggressive posture throughout British Palestine. None of these terms really apply to Wingate. Today, people speak of atrocities. But it is more helpful to understand what people are willing to do in the name of justice and against injustice. Wingate turned the secular Jewish partisans back to Gideon. The Special Night Squads were the formative event in the lives of some of the most important individuals in the history of Israel. No streets in Israel are named after Wavell or Dill. Some for Allenby, but most for Wingate. After Balfour, Wingate had the largest cultural impact on Israel. What did British, white, protestant, gentleman raised Orde Wingate think of the illiterate, tribal Arab farmers and shepherds? Very poorly.

In the years just prior to the Second World War, Wingate stumbled across an all too human problem in his own life, and came across what was a practical, if unexpected, solution. The solutions available to him depended entirely on previous life circumstances. As those solutions matured out of perceived necessity and into deliberate, planned action, their character--and the presumed character of their author--shifted, the way the sound of siren can sound different depending upon whether its vehicle is moving towards you, or moving away. In 1938, Wingate became a Zionist. Nothing about his previous experiences quite forecast his sudden determination to help European Jews establish a Palestinian homeland. We, in the twenty-first century, know of events that Wingate never lived to see, and so the word Zionism tastes clear and strong in our mouths, giving off flavors either bitter or sweet. For the British, the word lacked some (though not all) of its pungency in 1938. Here is the key fact to understanding Wingate's adoption of Zionism: It occurred in the company of his wife. He had sold himself as a man of action, and now had to prove it after months of relative indolence and sloth. The fallout from this impulse would bend (but not break) the Wingate marriage, and would permanently reshape their social and political interactions with their peers, followers, friends, and leaders. To understand Orde Wingate, one has to understand the stakes of war in the twentieth century. Those stakes are best understood in two measures: the first human and individualistic, and the second interstate and chaotic; the first is the most important. The stakes for individual human beings included the uncertainty of crashing governments and desecrated traditions; kings became paupers, lieutenants became generals, abject subjects became freedmen and tyrants.

Meanwhile, the world order collapsed and reformed without any definite end in sight. It began with the collapse of Tsarist Russia and the rush of bolshevism on cold steppes and basins; Marxism, like water down a wadi, poured forth with no fertile soil to soak up its precepts. Instead it cut the earth with Leninist interpretations, followed on with deeper cuts from Stalin; soon the waters began to dry, leaving a malformed ditch of communist collapse in the region least suited to thrive from the wash of its bright ideas. South of Russia, the Ottoman Empire's medieval bureaucracy, like that of Russia, failed the test of the First World War. It gave way to the pencil markings of the feverish, soon to take sick British Empire, France, and their local allies; the modern map of the Middle East has retained nearly the same fragmented aspect, despite the passage of a hundred years (Anderson, 2013). Italy and Japan allied themselves with Britain and France in the First World War; they suffered sleights both real and imaginary. Mussolini encouraged Italian efficiency and centralized state power, but he also mobilized puffed up armies who never mastered the force they so readily projected on parade grounds and against unindustrialized African states (Taylor, 1978). In imperial Japan, a generation of young officers seized control of the state and outbid one another in the sentiments of aggression (Taylor, 1978). The Japanese coterie rightly understood European colonialism prevented Japanese ascendancy as the dominant regional power, and that the United States would not allow them the natural resources necessary to challenge the European holdings. As the economic noose tightened, the Japanese kicked wildly at their American and European executioners. They inflicted blows, but ultimately knocked out the stool beneath their feet, and into the noose they fell; after the war, the Americans restored the stool. Failure was followed by submission, and an eventual rebirth. Meanwhile, China--the most significant victim of the bloody Japanese outburst--saw its own meager attempts at fascism collapse with the post-war defeat of the Chiang-Kai Shek government; the Maoists wiped the mainland Chinese state free of American intervention. Then Mao, like Lenin and Stalin before him, thrust the same Marxists waters down a different dry wadi; the death of Mao, and the eventual Soviet collapse, allowed Chinese communist party leaders to adapt to the rapidly changing global environment without a sudden loss of power. Three-thousand miles west of Japan, India chaffed under the increasingly ill fit of colonial rule; the reckoning of the Second World War shattered the final confidence of the British Empire--the same empire that Wingate was fated to die for. Wingate served across the wide world in the service of the British Empire. By mid-century it was a political body clawing for survival in the last years of life, sinking tired claws into its furthest outposts, ismuths, and islands. The empire failed the local peoples it promised to protect, and its vulnerability sent shockwaves that shattered generations of expectations (Bayly & Harper, 2004). The continents of South America and Africa, though not spared intervention and exploitation, saw unprecedented gains in population. Latin America and the Caribbean witnessed seven-fold growth, to upwards of 521,000,000 persons. Africa's population climbed six-fold to 800,000,000 ("Geohive," 2011). A friend once suggested to me that personal stakes are higher than political stakes; but political stakes are personal; in times of peace this requires wit to notice, but in times of war it is unflinchingly obvious. Political life dictates not only what you can get, but shapes what you can want, think, and feel; politics shapes who you desire and, having obtained your desires, politics determines under what conditions you will keep them and for how long. Politics can shorten your attention span, heighten your aggression, mitigate (or exacerbate) your fear. Politics can seem a toy, a plaything, a luxury. But politics is as inescapable as breathing--as are, incidentally, toys, playthings, and luxuries. We are the sum of our activity, not a severable aspect. The great political stakes of the 20th century shaped the personal views and ambitions of people like Orde Wingate--not the other way around. I have been thinking of poems about sailors over the past few days, and posting a copy of Tennyson's 'Ulysses' seems like the natural way to mark the process.

For me, the poem ultimately describes the social and psychological challenges of evading despair. When trying to avoid our own suffering, we often hurt those around us, as I think Ulysses does in this poem when he abandons his 'aged wife' and 'savage race;' he chooses to return to the ocean, and more importantly, into the wonderful unknown. He anticipates a rush of adrenaline, and a return to the adventures that occupied the twenty years that are partially depicted in Homer's Iliad and Odyssey. Ulysses' decision is a social challenge because he abdicates his responsibilities as a king, a father, and a husband; the monologue also suggests that he is rallying his sailors around him so that they can all continue the journey together--I wonder if anyone tries to remind them about the cyclops. Ulysses' decision is also a psychological challenge because his effort to revive his youthful mentality may very well fail. Is he still, as he promises, strong in will ? The poem's final iambic line strikes such a powerful rhythm that is almost impossible not to believe him. To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield. Tennyson, like us, may have found Ulysses' last line too seductive to find another ending. Ulysses BY ALFRED, LORD TENNYSON It little profits that an idle king, By this still hearth, among these barren crags, Match'd with an aged wife, I mete and dole Unequal laws unto a savage race, That hoard, and sleep, and feed, and know not me. I cannot rest from travel: I will drink Life to the lees: All times I have enjoy'd Greatly, have suffer'd greatly, both with those That loved me, and alone, on shore, and when Thro' scudding drifts the rainy Hyades Vext the dim sea: I am become a name; For always roaming with a hungry heart Much have I seen and known; cities of men And manners, climates, councils, governments, Myself not least, but honour'd of them all; And drunk delight of battle with my peers, Far on the ringing plains of windy Troy. I am a part of all that I have met; Yet all experience is an arch wherethro' Gleams that untravell'd world whose margin fades For ever and forever when I move. How dull it is to pause, to make an end, To rust unburnish'd, not to shine in use! As tho' to breathe were life! Life piled on life Were all too little, and of one to me Little remains: but every hour is saved From that eternal silence, something more, A bringer of new things; and vile it were For some three suns to store and hoard myself, And this gray spirit yearning in desire To follow knowledge like a sinking star, Beyond the utmost bound of human thought. This is my son, mine own Telemachus, To whom I leave the sceptre and the isle,-- Well-loved of me, discerning to fulfil This labour, by slow prudence to make mild A rugged people, and thro' soft degrees Subdue them to the useful and the good. Most blameless is he, centred in the sphere Of common duties, decent not to fail In offices of tenderness, and pay Meet adoration to my household gods, When I am gone. He works his work, I mine. There lies the port; the vessel puffs her sail: There gloom the dark, broad seas. My mariners, Souls that have toil'd, and wrought, and thought with me-- That ever with a frolic welcome took The thunder and the sunshine, and opposed Free hearts, free foreheads—you and I are old; Old age hath yet his honour and his toil; Death closes all: but something ere the end, Some work of noble note, may yet be done, Not unbecoming men that strove with Gods. The lights begin to twinkle from the rocks: The long day wanes: the slow moon climbs: the deep Moans round with many voices. Come, my friends, 'T is not too late to seek a newer world. Push off, and sitting well in order smite The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths Of all the western stars, until I die. It may be that the gulfs will wash us down: It may be we shall touch the Happy Isles, And see the great Achilles, whom we knew. Tho' much is taken, much abides; and tho' We are not now that strength which in old days Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are; One equal temper of heroic hearts, Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield. In collaboration with Humanities Texas and Chess Theatre Company, I am presenting George Farquhar's THE RECRUITING OFFICER as a part of the Veterans' Voices play series. Isto Barton will be directing a select group of am-dram performers in a two hour celebration of Farquhar's comic masterpiece--a play that smiles at the occasionally crooked relationship between soldiers and society.

The staged reading takes place the Byrne-Reed House in Austin, Texas, at 7:30pm. Reception at 7pm. Discussion should wrap up by 10pm.  Ari Shavit, My Promised Land, New York: Spiegel and Grau of Random House Publishing (2013). The nation of Israel, the last great colonial enterprise of the Western world, exists in a harsh, hot climate, surrounded by enemies that deny it a right to exist. For years, it served as beacon of democracy and Western military supremacy, but now it threatens to fall into theocracy and political isolation. Israeli journalist Ari Shavit presents his own personal history of Israel with My Promised Land, a fast-reading account of a young nation's struggles along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea. Shavit drives his narrative forward with extensive interviews. Many of his discussions feature the complex heroes and villains of the Zionist enterprise: settlers, warriors, and spies; capitalists, socialists, and politicians. Though he cuts the interviews with dashes of biography, historical context, and personal reflection, in the main Shavit allows his protagonists to co-author his book, so that they can defend their hopes, dreams, and doubts. Shavit begins with a chapter out of his own family history. In the closing moments of the nineteenth century, an English-Jewish ancestor visited Palestine for the first time. He surveyed the countryside, and settled there a few years later. The Jewish settlers of the late 19th century tackled the problem of creating a Jewish homeland in a way similar to other herculean colonial enterprises, such as the Suez Canal; they raised capital from abroad, and then added tremendous amounts of human labor. They bought land from the waning elite of the Ottoman Empire. When necessary, they forced the removal of the serfs and tribes that had occupied the land for centuries. Intellectually, the Jewish immigrants felt tied to Europe, but they knew that Europe no longer wanted them; in the desert they began to forge a new identity, one with less room for the individual spirit and conscience, and much more aggressive than what they inherited from their diaspora ancestors. The European Jews, imitating European colonial powers, looked at Palestine as a backwards, empty land. They never saw the Arabs as inhabitants. They only saw an empty land open to the aspirations of Jewish nationalism. The Jewish settlers especially sought out the rich coastal soils of Palestine. They wanted collective economic success and secular socialism, not the restoration of Biblical landmarks in the hills to the east. In time, the disenfranchised Arab serfs began to push back against the newcomers with sporadic murders and assaults on Jewish settlements. The Jews responded to the violence with calls for the forced migration of Arabs out of Palestine. By 1938, the language of David Ben Gurion echoed that of world leaders working elsewhere: "I support compulsory transfer. I do not see anything immoral in it." Shavit then traces how individuals like Shmaryahu Gutman drew on ancient Jewish symbols of resistance, like the mass suicide at the Masada fortress in 73 CE, thus "using the Hebrew past to give depth to the Hebrew present and enable it to face the Hebrew future." A rootless nation searched for its Hebrew past like a long forgotten spring and, once rediscovered, held onto those ancient waters with emotions that tottered between tenacity and desperation. Jewish survival in Palestine required collective organization for social, political, and military conquest. The end of the British Mandate heralded a new era of Zionism. The Zionist political leaders rushed into action in 1948 and sliced off a portion of the region designed to ensure a Jewish majority in the newborn country of Israel. Shavit cannot help but look back at his country's history with awe, love, and pride--and so Shavit's presentation is as personal as it is insightful. As a journalist he expands that history by inserting the memories, fears, and dreams of other Israelis. His emotional exploration of Palestine brings with it a humor and sadness all its own, one that fights against the coldness of a historical narrative. Perhaps his most effective chapter relates the crisis of Lydda, 1948, in its absolute tragedy. The fatigued, desperate Jewish soldiers scrambled to the very edge of the Arab village of Lydda. And then, assuming the worst, the soldiers (including Moshe Dayan) charged through town with armored vehicles, guns blazing. Israel's founding political leaders abstained from making a clear decision to force the removal of the Arabs from the village, thus preserving their reputation in Europe and America. The absence of oversight turned their young Israeli soldiers into aimless cannons which the Arab civilians had to dodge through flight. The Arabs abandoned their dignity and homes for the sake of momentary security, and straggled out of Lydda (and many other villages) on long, deadly marches. Throughout the early years of Israel, trepidation gnawed at the backbone of Jews and Arabs alike, prompting them to edge deeper into the depths of human behavior. Interestingly, Shavit mourns the loss of the Israeli character that inspired Zionism in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. "On the one hand [Zionism] was a colonialist enterprise. It intended to save the lives of one people by the dispossession of another. In its first fifty years, Zionism was aware of this complexity and acted accordingly...but after 1967, and after 1973, all that changed...." The victories and traumas of 1967 and 1973 forever altered the political landscape of the Middle East, and the social fabric of Israeli society. Israel initiated the Six Day War of 1967 to create a political buffer between themselves and the surrounding Arab nations, and in anticipation of an Arab attack just over the horizon. Israel caught its rivals completely off guard, and won the war with superior preparation and complete surprise. The victories of 1967 left Israel drunk with victory, and far more land than they had hoped for at the outset of their enterprise. The occupied territories soon complicated the problems of Zionism. Many defeated Arabs were unable to immigrate to another country, and to this day they remain imprisoned in small tracts of land in Gaza and the West Bank. Though tragic and inhumane, the experiences in Gaza and the West Bank are not a second Holocaust. As Shavit says, 'no one can seriously think there is any real similarity. The problem is that there isn't enough lack of similarity. The lack of similarity is not strong enough to silence once and for all the evil echoes." And so the Israelis live in close and dangerous proximity to the people they displaced, and those people watch them day after day. The Israelis look back with wary eyes, "the jailers imprisoned by their jail." Israelis desperately want to believe in their country--their nation--as established fact. They want release from the terrible fear that haunts the low-land orchards, the ancient alleys of Jerusalem, and the drug-soaked discotechs of Tel Aviv. But Shavit sees no release from the fear. Modern Israelis lack the secular hardness of their grandparents and great-grandparents. The melting pot of 1948 now congeals into separate small-minded elements: right-wing, left-wing, Oriental Jew, ultra-orthodox, capitalists, settlers, and rootless Palestinian refugees. The soft selfishness of individualism undermines the collective consciousness necessary for survival in the Middle East. He anticipates a second Holocaust, easier than the first due to the small spot of land upon which the Jews now live, and the tools of nuclear destruction that he believes will soon sprout among Israel's many Arab neighbors. Shavit repeatedly calls his book a personal history. He offers somewhat skewed interpretations of many key events. For example, he calls the 1936 Arab revolt "a collective uprising of a national Arab-Palestinian movement," but leaves the revolt poorly explained and poorly reasoned, ignoring the way that economic modernization can threaten tribal honor; he also never identifies the key leaders of the revolt, or their localized motives. Yet Shavit writes with a journalistic candor, and he conveys epic history. To tell his story, he chooses certain perspectives and subjects as stepping stones along the path. My Promised Land, therefore, never presumes to be a comprehensive volume. It assumes knowledge of pivotal figures like David Ben-Gurion, Moshe Dayan, and Golda Meir. It also assumes a familiarity with British colonialism, the First and Second Worlds Wars, and the conflicts of 1948, 1967, and 1973. Yet Shavit's use of expanded, effusive stanzas of dialogue help paint the story of Israel in powerful, nuanced strokes of darkness and light.  John Keegan, The Face of Battle. New York: Penguin, 1978. In the Face of Battle, John Keegan explores the experience of soldiering in three significant (and very different) battlefields from British history. He begins with the mud, steel, chivalric culture of Agincourt. The pages turn, and soon the massive infantry squares appear through the gun-smoke shrouds of Waterloo. A century later, hundreds of thousands of soldiers die among the wire and trenches of the Somme. Keegan adopts a rapidly moving third-person perspective to tell the story of each battle. The book's unusual structure helps Keegan peer deep into the mechanisms of organized violence. He examines the decision-making of generals, but frequently leaves the generals behind to focus on the what the great masses of troops actually saw and did during their respective battles. He examines the weapons and armor of the participants, but also asks about their hometowns and moral outlook. He differentiates between the officers and the enlisted soldiers, and while he does not ask about the source of class divisions, he shows enough interest in them to suggest how such divisions effect behavior on the battlefield. For each battle, he opens with a short examination of the battle's larger context--or at least the campaign of which it was a part. He then examines the particulars of the battle, with its turns, stages, and outcomes. He then assesses the practicalities of the various matchups that occurred. In Agincourt, for example, he asks how archers fared against infantry and cavalry, and what close-combat looked like to an infantryman in 1415. After examining the action, he addresses particular moral puzzles that each arise during each battle. Why did Henry V demand the execution of his French prisoners? Why did the British leave their wounded on the field at Waterloo? Why did soldiers of the First World War propel themselves out of the trenches and into harm's way? He takes what he learns from all this and applies it to a final chapter, where he considers the future of war, and the changes of technology that effect it; he ultimately supposes that war will grow increasingly horrific, regardless of the perks and amenities nations attempt to provide their armies, such as pensions and air conditioned tanks. Keegan's book celebrates its three battles as moments of human interest, filled with deep failings and horrific exaltations. His emphasis on personal action and individual decision-making wins steep dividends. He recognizes that "ordinary soldiers do not think of themselves, in life-and-death situations, as subordinate members of whatever formal military organization it is to which authority has assigned them, but as equals within a very tiny group...." As a consequence, much of battle consists of leaders attempting to hold individuals to a collective fate, while at the same time trying to break the will of individuals in the opposing force. Thus, he pays keen attention to why Napolean's heavy cavalry units never quite crossed swords with the British infantry squares, but instead skirted their ranks, fled, and charged again. And he shows that French men-at-arms avoided confronting archers, not necessarily because of the danger archers presented, but because could find no honor or monetary reward for attacking and capturing individuals from such a low station. Keegan, in short, unpacks the physical and psychological effects of warfare from the perspective of the individual, and then assesses the gritty details that make warfare so untenable, yet so horribly persistent throughout the years. As a work of history, Keegan grounds it in three very specific times and places, rather than attempting a generalized psychological exploration of organized violence. It is all the more convincing for his deliberate attempts to evoke specific moments in history: the mud-choked rise of infantry from the trenches, the screaming of horses before a fully-formed square. |

AuthorJ. M. Meyer is a playwright and social scientist studying at the University of Texas at Austin. Archives

July 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed