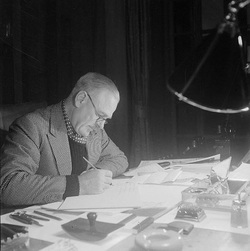

In an earlier entry I reviewed The Viceroy’s Journal. The book made me a fan of its author, Viceroy Archibald Wavell. His frankness cuts ice like butter. And even when he finds himself on the wrong side of popular history, he paces himself through his actions with a disarming insistence on decency.

Like most generals of his generation, the First World War shaped his behavior in the Second, and in the intervening years. Many survivors of the First World War turned against the military and government service altogether, but Wavell’s early education and stoic coolness combined to ensure that he would serve his country for life. He could not speak off the cuff very well, but he wrote eloquently and effectively in private. He also published two popular works. The first was Generals and Generalship, derived from a pair of formal lectures he gave at Cambridge. The other was Other Men’s Flowers, a collection of all the poems that Wavell memorized throughout his life. Both of the slim books proved popular with soldiers during the Second World War.

Early on in his career, Wavell served as a personal liaison to General Sir Edmund Allenby. Wavell viewed Allenby as a mentor and role model. Allenby navigated a difficult political environment in Egypt at the close of the First World War. Much to Churchill’s chagrin, Wavell’s liberal tendencies and experiences under Allenby gave him the wherewithal to take an active role in Indian independence rather than passively waiting for the end of the Second World War. As Viceroy, Wavell saw his duty as careful balancing act: managing a transitional phase of Indian governance without undermining the precarious position of Britain’s war leader, Winston Churchill.

Serving under Allenby also gave Wavell the opportunity to see the value of experimentation and risk taking in warfare; Allenby led the allied forces to victory against the Turks with limited resources and a great deal of unconventional support.

Wavell played a crucial role in Wingate’s development as a battlefield commander. The start of this came in July 1937, when the Army placed Wavell in command of forces in Palestine and Transjordan. Arab unrest led to outbreaks of violence against both British troops and Israeli settlers shortly thereafter. Wingate, assigned to a relatively minor role as an intelligence staff officer, flagged down Wavell’s car and pitched to him his idea for Special Night Squads to defend Israeli settlements against violent attack. Wavell’s acquiescence to Wingate’s request provided Wingate his first opportunity to train unconventional forces and fight in combat.

Wavell made use of Wingate on two more occasions, first in Abyssinia against the Italians, and then in Burma against the Japanese.

The following notations about Wingate come from the book Viceroy’s Journal, as edited by Penderel Moon. I have shaped my quotes so that they demonstrate something of Wavell’s character and interests, and therefore the quotes are not as direct as they might otherwise be.

The following entries understate Wavell’s personal entanglement with Wingate and the Chindits. Brigadier Bernard Fergusson, mentioned in the December 29, 1943 and May 8, 1944 entries, later wrote a short biography of Wavell, as well as an account of Chindit operations called Beyond the Chindwin. Additionally, Wavell’s son, Archie John Wavell, was an officer in the Black Watch, one of the key units under Wingate’s command during Operation Thursday in March 1944.

******

[Pg 15] August 23, 1943.

Cabinet meeting with 2nd XI present, practically all 1st XI being still in Canada. Proposal to appoint Mounbatten to the S.E. Asia Command, with Stilwell as Deputy, and Giffard as commander of Land Forces, was announced. There was some criticism but general feeling was that appointment should be accepted since Chiefs of Staff and Americans approve.

P.M. is still in Quebec. I hear that Wingate has apparently ‘sold himself’ well there and his ideas are to havea good run. I expect P.M. will now claim him as his discovery and ignore the fact that I have twice used Wingate in this war for unorthodox campaigns and that but for me he would probably never have been heard of. I gather they are at last realizing the difficulty of communications in Assam and Burma which I have been trying to impress on P. M. for nearly two years.

[Pg 37] November 17, 1943.

M.B. [Mountbatten] came again on 15th to tell me about the Cairo meeting… we also spoke of the parachute demand; he still seems to think that to double the demand (from 100,000 to 200,000 [per month], the original demand having been 35,000) is a mere trifle for India; as it only meant giving up 2% total cloth: I pointed out that 2% of India’s population was 8,000,000 which was quite a large number to go short of clothes.

Wingate left today after convalescing here for a week. He a little reminds me of T. E. Lawrence but lacks his sense of humour and wide knowledge, is more limited but with greater driving power.

[Pg 43] December 29, 1943.

Bernard Fergusson turned up unexpectedly yesterday evening for an ight, and I had a talk with him about his experiences with 77 Bde in Burma. He says the venture was well worth while, and that Wingate’s theories are right, though the troops did not do all that Wingate claimed that they did. He said Wingate was, and is, extremely difficult—impossible at times—and he had many rows with him, but he still believes in his ideas. He was apprehensive about his forthcoming role, if he had to go in and come out again as he did not feel we could abandon the Burmans who helped us to the vengeance of the Japanese a second time…

[Pg 60] March 18, 1944.

Saw both M.B. [Mountbatten] and [Lt.-Gen. Sir Henry] Ponwall and talked to them of situation on Burma frontier. It shows the respect they have for the Japaense tactics and fighting that though they have something like twice the Japanese strength available ion the Chin Hills-Chindwin-Manipur front and have known for months that the enemy were about to attack, they are both feeling rather apprehensive of the result; and have taken aircraft off the ferry route to China to fly into Manipur another division from Arakan. The 17th Division is being pulled back from Tiddim area by Japanese action against their communications, although in numbers we must be superior. How does the Jap do it? The simple answer ist hat we have a very ponderous L of C [Line of Communication] and the Jap has practically none at all; we fight with the idea of ultimate survival, the Jap seems to fight with the idea of ultimate death and contempt for it, when has done as much harm as possible. The flying in of Wingate’s two brigades [Operation ‘Thursday’] seems to have been a remarkable performance after an initial set-back in which there were about 150 casualties from crashed or lost gliders. But so far the Jap appears to have taken no notice of this force in his rear, his independence of communications is remarkable.

M.B. is prepared to back me up on food problem and agrees that Americans must be told the situation officially if H.M.G. will not find imports. [reference to the Bengali Famine.]

[Pg 61-62] March 28, 1944.

Last day or two comparatively quiet, usual interviews and papers, but I have actually managed to find a little time to work on the dispatch I ought to have written as C-in-C last year… The C-in-C spoke of the fighting on the Assam border where the Japs seem to be making headway. Large numbers of our troops are being concentrated in Assam, including I think 2nd Division; this will throw a very heavy strain on communications.

Was told later in the morning that Wingate was missing from an air trip over Burma. I heard later that he had almost certainly been killed in an air crash between Imphal and Silchar.

[Pg 69-70] May 8, 1944.

I got back yesterday from a short tour to Sikikim. A long days travel on May 2; left Delhi 6 a.m., landed Hassimara about noon and then had to cross a river by elephants, a flood having taken the bridge. Then a long motor drive to Gagtok were we arrived at 9 p.m…

I left Gagntok on May 6th and flew to Sylhet in Assam. I spent the night at Sylet and visited H.Q. 3rd Indian Division—the headquarters of what were Wingate’s raiding columns, now Lengtaigne’s [Maj.-Gen. Lentaigne]. Lentaigne is good, I think, more orthodox and less highly strung than Wingate, who possible was killed at the right moment both for his fame and the safety of the division. But he was a remarkable man and I am glad that I was responsible for giving him his chance and encouraging him. My dealings with him, in three campaigns, were almost entirely official and I never knew him well enough to like or dislike him.

I had hoped to see [my son] Archie John but he had flown into Burma a week before. Tired of waiting for vacancy in the Black Watch he had taken one in the South Straffords. I believe the column he has joined is likely to be flown out soon, but I expect Archie John will try to stay on with his own regiment or some other column. I hope his health will stand it. I saw Bernard Fergusson, complete with bushy beard, whose brigade had just been flown out. He was well, but a little upset by his failure to win his first pitched battle, at Indaw against the Jap airfield. He had had a hard time marching down from Ledo through the jungle, said it was surely the only recorded instance of a brigade marching 250 miles in single file.

We had a long fly back, nearly 7 hours, as we were in a slow machine, and did not reach Delhi till nearly 7.45 p.m.

-------------------------------------- --------------------------------

Sources:

Fergusson, Bernard, rev. Robert O'Neill, and Judith M. Brown. “Wavell, Archibald Percival, first Earl Wavell (1883–1950).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. OUP 2004-2013.

Wavell, Archibald Percival. The Viceroy’s Journal. Ed. by Penderel Moon. OUP, 1973.

Sykes, Christopher. Orde Wingate: A Biography. The World Publishing Company, 1959.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed