|

John M. Meyer (2022) '"Nor doth this wood lack worlds of company:” the American Performance of Shakespeare and the White-Washing of Political Geography," Multicultural Shakespeare, vol. 26 (41), 119-146, DOI: 10.18778/2083-8530.26.08. Peer-reviewed.

0 Comments

Afghanistan is one of those topics in which lies are told as soon as you've determined to make it your subject.

Up next from Thinkery & Verse: AFTERSHOCK / LA RÉPLICA w/ Teatro Vivo and Canopy Theatricals at the MACC, ATX November 14-24 AFTERSHOCK / LA RÉPLICA is a world premiere stage-play that explores new dimensions of Latinx military service.

The Latinx soldiers and citizens in this play expect military service to reinforce their identity and ideas about family, patriotism, and even sexuality, but the military is often a place that mixes up the moral compass, and one’s sense of self, and invents a new identity. The script draws on first-person narratives, interviews, archival sources, Latinx poetry, veteran writings, rumors, legends, and some of the best ATX imaginations. Thinkery & Verse, Teatro Vivo, Canopy Theatre, and ArtSpark are proud to be a part of the Austin Veteran Arts Festival - AVAFest at the Emma S. Barrientos Mexican American Cultural Center. Austin's only theater venue located in the lightning hot Rainey Street district.

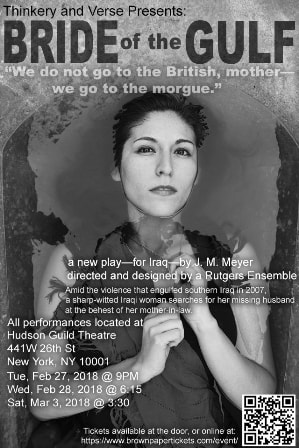

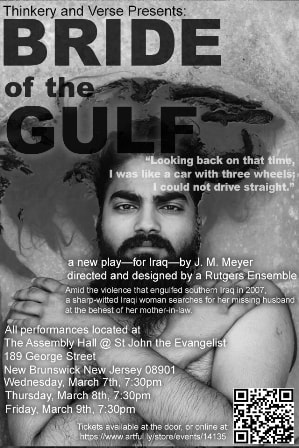

I am honored and amazed that BRIDE OF THE GULF is getting a chance to go to the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. This play has been on an interesting, and sometimes fraught journey, but I am so proud of Thinkery & Verse, Fort Point Theatre Channel, our friends in Basra, Rutgers University, and all of the other people who have helped make this play possible. I am above all thankful to Karen Alvarado for pushing ahead with this project when I was ready to put it to the side. She's a true artist. You can catch our play at C Cubed Main, just off the Royal Mile, starting August 2nd and running until August 27th. All performances begin at 3:10pm. If you're in the UK, I hope you will stop by and see us. A big thank you to C Venues, and to the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. When our fundraiser reached the $1,000 mark, Thinkery & Verse had me pen a quick description of the project in its early stages. It seems appropriate to share that information here. BRIDE OF THE GULF began in 2016, not just with Thinkery & Verse, but as a short play for Fort Point Theatre Channel. The playwright Amy Merrill invited me aboard the team, and then two of the co-artistic directors, Anne Loyer and Marc S. Miller, asked me to collaborate with two musicians, Qais Ouda (Basra, Iraq) and Jorrit Dijkstra (Boston, MA). Amir Al-Azraki, an Iraqi-Canadian playwright based in Toronto, facilitated the dialogue; the project, I think, is a tribute to Amir's patience, as he facilitated not only our work, but that of the other groups as well.

Those conversations, e-mails, and listening sessions led to the vibe of BRIDE OF THE GULF. The short play had more breathing room than I leave in some of my plays because I left space for music and movement. In theater-criticism and pop culture the term 'melodrama' has a negative connotation because most plays and films use music to control the audiences' emotions; music is often manipulative, and sometimes cloying. But in this case we needed music to open the door to more abstract forms of representation; the musicians, consciously or not, encouraged me to write 'impossible' stage directions. Here's how the first version of the play began: [Lights. Everyone on stage is newly dead, burnt crispy, bloody, or simply gone, and awkwardly posed, including HERO, a young woman. Hero opens her eyes.] HERO: Saddam Hussein lasted 24 years. He hated Basra, the city I was born in. He used to say, "Basra is the bride of the gulf, but she's a peasant; peasant brides deserve three days of nice treatment, and then chase them to the fields." By the year 2016 it has been thirteen years since the invasion of Iraq removed Saddam Hussein from power. [Hero sits up.] HERO Despite the violence of this period, we are not all dead. [Everyone gets up and starts cleaning off the blood and filth.][A woman studies law. A man goes shopping. Two young people play draughts. A young man and young woman assemble a machine gun. Two young militiamen setup an 82mm mortar.] HERO In 1987, we had a population of perhaps 400,000. Now, despite all of the thirst, the starvation, the hate, and the death that has transpired in the intervening years... [The two young militiamen launch a mortar round, which vanishes in an explosion.] HERO ...we number more than one million people. It was not a magic trick. We just kept having sex and kept having babies.... ******* In the piece above, Hero, a young woman, opens the play. She and her countrymen appear dead, which is how most Americans seem to think of the Middle East. I chose not to give her any other name because I wanted the actors to take her seriously as a protagonist--as a hero. She has desires, dreams, goals, and a point of view. In Hero's case, she wants to find her husband (a translator for the British Army) so that they can have a child together or, barring that, to kill him for trying to abandon her. Hero is smart and knowledgeable. Like most of the characters in the play, she is a composite of people I knew in Iraq, some translators, some Iraqi government officials, and some people that we were pretty sure were trying to kill us. Others quietly wished that we were not there at all. But we all shared in the awful experience of Iraq as it teetered on the brink of civil war, and it was impossible not to admire the perseverance of my Iraqi friends, contacts, and acquaintances. In my time there, it became very apparent that the Americans and British were far less powerful and influential than we perceived ourselves to be. In creating the short play alongside Fort Point Theatre Channel, director Kathryn Howell, and Karen Alvarado, we were not trying to rewrite the impending future, or change the world. We simply wanted actors and audiences to briefly join us for twenty minutes in imagining what the invasion of Iraq might have looked like from the other side. In the longer, full-length version of the play--the play we are taking to Edinburgh--we go past that and we 'frame' the story-telling. That aspect of the play developed out of subsequent collaborations with English students in Basra, Iraq, and with conservatory artists from Rutgers University.

Hi Johnny,

My name is C. Stephenson--I met you briefly during one of your visits to Lawrence. Anyway, I am the dramaturg for the B'srd Shrts and I am currently compiling playwright bio's for the program, and we thought it would be kind of snarky to do an interview format for your bio, since you are alive. (Also, I know Churchill is alive... but I can only manage so much :]) If that is okay with you, I was wondering if an e-mail format for the interview would be okay, as I'm not sure I could set up a phone interview quickly enough. If so, let me know and I'll e-mail you back a document with the questions that you can fill in. Also please feel free to add anything pertaining to yourself as a playwright or simply as a person that you would like to be included. I have a small bio from Kathy and Tim I've looked at so hopefully I'll be able to cover a good amount. Thanks, C. Stephenson --------------------------------------------------------------------- Hi C., Why don't you fire away, and we'll see how it goes? J. M. --------------------------------------------------------------------- Thanks for the quick response. Alright, firing away: Q: Okay, I have to ask the typical protocol bio question of: Where were you born, when were you born, where did you grow up and does that or your family have any influence on your writing/authorship? Q: Favorite playwright? Favorite absurdist playwright? Q: What style is your typical go to style for playwrighting, or do you take the Churchill/Beckett “can’t categorize me” approach? Q: Thanks for serving in the military— I have the utmost respect for you, I come from a long line of servicemen. How much does that influence or seep into your dialogue/themes? I can’t imagine a life experience at that caliber not finding its way into your art in some way. I am a new mom and I find even when I try not too, essences of that find their way into my scripts. Q: What’s your biggest pet peeve in life or as an artist? Q: Would you rather go to lunch with Samuel Beckett or Artaud? Care to explain? I think each would provide polarizing opposite effects. Q: Can you give a little overview of your process and approach to Cryptomnesia, or would that be a disservice to the show itself? Was there an object, idea, movement, etc. that influenced the creation? Q: Do you have a hidden talent? Q: If you could trade places with any person in history, dead or alive, who would it be? Such a lame question, but I think it says a lot. Q: Anything else you’d like to share? Thanks for baring with my horribly cliche questions, I didn't have adequate time to prepare a nice thoroughly thought out interview. I'll conduct a better one if you're around during production--keep it in the dramaturgy notebook. Thanks, C. Stephenson --------------------------------------------------------------------- Q: Okay, I have to ask the typical protocol bio question of: Where were you born, when were you born, where did you grow up and does that or your family have any influence on your writing/authorship? I was born in Dallas, Texas in 1982. I grew up in Dallas, New Orleans, and Kansas City. I am sure that my childhood shapes my plays. I am the oldest child in a family with three sons and three daughters. My parents are Roman Catholic, or at least what passes for Roman Catholicism in the United States. Social context and family play decisive roles in shaping who we are, but writing is more specific than living because with writing we can edit, revise, and manufacture our wares. A short play like Cryptomnesia can only share the smallest fraction of common ground with its playwright. Q: Favorite playwright? Favorite absurdist playwright? My favorite playwright, the playwright I spend the most time with, is Shakespeare. The tag 'absurdist' is more useful for audience members and critics than it is for the playwright or other artists; it helps audience members approach a piece with a certain wariness, and perhaps an openness to incredulity. One of my other favorite playwrights is Christopher Marlowe, Shakespeare's contemporary and stylistic predecessor; I suppose I adopt an 'absurdist' framework when watching his plays, which I usually enjoy. Of the twentieth century playwrights, the works of Samuel Beckett remain the most accessible thanks to the 'Beckett on Film' series. But if I have a preference for Beckett over, say, Churchill or Albee, that probably has more to do with convenience and accessibility than it does with aesthetics. Q: What style is your typical go to style for playwrighting, or do you take the Churchill/Beckett “can’t categorize me” approach? Do they say that? Or, from a creative place, do they simply find 'style' unhelpful? If Churchill labeled herself 'absurdist,' she might not have written plays like Top Girls or Serious Money. Q: Thanks for serving in the military— I have the utmost respect for you, I come from a long line of servicemen. How much does that influence or seep into your dialogue/themes? I can’t imagine a life experience at that caliber not finding its way into your art in some way. I am a new mom and I find even when I try not to, essences of that find their way into my scripts. What I saw and did in Iraq and Afghanistan alienated me from America. I mourn the disconnect between what we are, and what we could have been. I am very lucky, in that I have travelled through most of America, and much of the world, and have had the chance to respond to it. But when it comes to absurdism, I think it is more helpful to ask audience members, 'How do your own personal experiences shape your reaction what you are watching, listening, and feeling?' The playwright must be a little hands off; what we're making in Cryptomnesia is aesthetically closer to a mirror than to autobiography. It's not a landscape, or a character sketch, or a history. The fact that human beings are capable of observing absurdist theater and responding to it intelligently is almost a miracle. But however they respond to it, that response probably has more to do with who they are and where they are from than anything else. The artists and the playwright anticipate the audience, but cannot lead them with a hook or tether. Q: What’s your biggest pet peeve in life or as an artist? Distracted acting. Waiting for laughs. Carelessness with handguns. The incessant meowing of cats. Q: Would you rather go to lunch with Samuel Beckett or Artaud? Care to explain? I think each would provide polarizing opposite effects. Artaud has been dead much longer, and I think his advanced decomposition would be least likely to spoil my lunch. Q: Can you give a little overview of your process and approach to Cryptomnesia, or would that be a disservice to the show itself? Was there an object, idea, movement, etc. that influenced the creation? When Tim commissioned the play, he asked me to think about what 'absurdism' might mean to students at Lawrence University. Last fall, I had the chance to survey the campus, sit in on classes, and meet the students. I also explored the university's past, and tried to understand what it looked like to the people in the present. And, truth be told, I found I really liked Lawrence University. I had never been to a liberal arts college. I enjoyed the experience, and enjoyed observing what appeared to be the experience of the students and the professors. If absurdism involves some kind of confrontation with society--and I think it does--then my liking Lawrence presented a weird sort of dramaturgical problem. It took some work to get around that. Given the absence of obvious targets, I took a look at the individual 'person' who happens to be at Lawrence, and what they look like in the wider, less comforting society. Eventually I wound up with an observation, and two questions: As strong the local society might be, the individual is not necessarily able to remain in such a comfortable place. What might take them out of that society, and what are the personal costs thereof? That was the starting point. The starting point was a sort of complete McMansion; the next step was to destroy the roof, and tear out the drywall, and find out if anything was alive beneath the carpeting and inside the frame of the house. Q: Anything else you’d like to share? Yes, I suppose I would like to offer a few words about the other playwrights, and where I feel absurdism comes from. A popular definition of 'absurd' proposes 'crazy, unreasonable, untimely' as a suitable meaning for the word. The aesthetics of absurdism suggest mystery, confusion, and perhaps 'cutting-edge' theatrics, but the artists associated with absurdism spend an awful lot of its time looking mournfully backwards. Antonin Artaud named his theater after a French playwright of the previous generation (Alfred Jarry), and Artaud harvests his damaged characters from deep in the European past. Samuel Beckett pulls many of his images from the devastated landscapes of the Second World War, and his characters incessantly attempt to remember--remember what? a story? a person? How exactly did they tumble into their current situation? How can they get it right? How can they do it better next time? Whereas Artaud offers visual ecstasy and religious voyeurism, Beckett offers comic circles and tragic cynicism. As a whole, the plays of Caryl Churchill defy any particular emotional landscape, through she also looks backwards towards realism and naturalism. Her play This is a Chair seems to reference the late twenties French painting called La trahison des images. The painting shows us a pipe, but is helpfully labeled, Ceci n'est pas une pipe: "This is not a pipe." And of course the label on the painting is correct; it is not a pipe, but rather a painting. But This is a Chair. Churchill explores the spongy limits of realism, the darkness that surrounds the everyday people that democratic-capitalism panders to. The three writers--Artaud, Beckett, Churchill--find themselves in a crazy, unreasonable, untimely moment. Whatever it is that they were looking for in their youths, it was not quite there, and the experience of its absence granted no secret wisdom that can help the next generation do any better. Comic circles, tragic cynicism. Realism with spongy limits. Visual ecstasy and religious voyeurism. The techniques and mysteries of these writers trace back to the witches of Macbeth, Shakespeare's soliloquies, and the clipped in media res epics of Homer. But while these writers are decidedly Western in thought and action, one can also look further afield in the wide world and find theatrical art with a kindred spirit; the rhythmic mysteries of Noh drama come to mind, where the key 'event' of the play can involve an act listening, rather than an act of confrontation. There are others as well, but that's enough out of me. Over a six-month period in 2016 I held a fellowship at Bedlam, a New York theatre company, courtesy of The Mission Continues Program, a non-profit that helps provide fellowships to military veterans such as myself. During this same period, Bedlam received support for their outreach programming courtesy of the Theatre Communications Group. As a result of the support from TCG, Bedlam was asked to provide a short blog post describing their work with veterans. In turn, I was asked to write the post. It's a great program. I was thrilled that they asked me, and thrilled that they published it on the TCG website. And I was also excited to get the chance to showcase the writing of my good friend Lou Bullock--you will find his material in the second half of the post! Bedlam Outreach

blog post by J. M. Meyer At Bedlam Outreach's free Monday night classes, we study Shakespeare's texts, explore play and performance, and undertake writing exercises to help veterans discover how their politically involved and sometimes violent lives resonate with Shakespeare's plays. We help veterans discover what they learned about humanity from their military experience. And with Shakespeare's help, we also help veterans explore how their experience resonates within the broader Western culture that sent them to war. We have found that military veterans sometimes feel more at home in Shakespeare's tragedies and history plays than they do in 21st century New York. I am myself a military veteran, and a theater artist. I first came to Bedlam Outreach about two years ago. But before I ever moved to New York, I had heard of Bedlam's inventive, aggressively theatrical interpretations of classic plays. And as a teaching artist involved in connecting military veterans with humanities texts, I had also heard of Stephan Wolfert, Bedlam's Director of Outreach. Bedlam might be a new theater company, but it largely consists of experienced artists, and I think that might be why the focus and scope of their outreach program can comfortably include veterans. As one example, Stephan has been a teaching artist for more than twenty years. He left the military in the late 90s to study classical acting, first training at Trinity Rep, and then with Tina Packer at Shakespeare & Company. To join Bedlam, Stephan relocated to New York from Los Angeles, where he had founded the Veterans Center for the Performing Arts, and wrote his one-man play Cry Havoc (among many other projects). And as a second example, Eric Tucker, the founding artistic director of Bedlam, served in the Navy, and first worked with Stephan in graduate school. Since then, Eric has become one of the acclaimed interpreters of the classics of his generation, and just in the last few years he and his artists have created a Saint Joan that restored Shaw's comic sense of evenhanded ruthlessness, A Midsummer Night's Dream that reminds us that fantasy can be a synonym for nightmare, a double-take Twelfth Night that explores Shakespeare's language with the precision of a diamond cutter, and a Sense & Sensibility that puts social humiliation on wheels. To use Olivier's favorite phrase, Stephan and Eric have both been "jobbing actors" for a long time. Without this history of experience and military service among Bedlam's leadership, I doubt that Bedlam Outreach could have sustained its weekly efforts amidst the daily struggle for resources that every theater company endures. (It also helps that the Sheen Center generously opens their doors to us at below-market rates, that guest artists like me, Judy Molner, Alex Mallory and Tom O'Keefe kept the class going when Stephan could not be there, and that our managing director, Kimberly Pau Boston, is a playwright-producer with years of experience working with military veterans.) (Outreach is hard.) At any rate, Stephan and Eric both opened doors for me to learn from them, as they have to many other military veterans. They allowed me to undertake a Mission Continues Fellowship at Bedlam Outreach, and then encouraged me to teach some of the Monday night classes. This led to one of my proudest Outreach moments, which was an open house presentation of the monologues and short plays of Lou Bullock, a non-combat veteran from the Korean-war era. I suppose most people these days, when they try to imagine the typical military veteran, think of our recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan; therefore, they may not immediately imagine someone like Lou Bullock. This would be a serious mistake. The veteran population as a whole skews just a few years shy of the average age of retirement. As a consequence, a lot of our best work at Bedlam Outreach occurs when we engage with veterans in their fifties, sixties, seventies, or, in Lou Bullock's case, his eighties. (Up at Lincoln Center Education, Eric Booth and his fellow teaching artists sometimes refer to this kind of work as 'creative aging.' I love the phrase, though I can imagine our veterans rolling their eyes at a mild euphemism.) The demographics of our students, combined with the fact that we only meet once per week, help to dictate the kind of work Bedlam Outreach undertakes inside the rehearsal room. A lot of our veterans, for example, prefer not to memorize lines. They instead arrive at the Sheen Center each week 'open' to whatever exercises or Shakespeare scenes we can cook-up in a three hour time span. As a whole, the classes avoid the intensity of conservatory training, or the rigor of an academic study of Shakespeare's plays. Instead, we emphasize our veterans' immediate reactions to scene work, as well as their response to Shakespeare-inspired writing prompts. From time to time, however, we hold an open house to share the work of our veterans. In a couple of instances, our open houses celebrated the personal writings of two of our veterans, Lou Bullock (a skilled monologist and quirky scene writer), and Phil Milio (a Vietnam veteran and an introspective story-teller). I deeply believe in these sustained performance opportunities–they are my favorite part of Bedlam Outreach, because I never feel a greater sense of camaraderie than when I witness (or work towards) the art of watching and being watched in the crash-course of public performance. At Bedlam Outreach, we believe in the power of the performing arts to help reintegrate veterans into civilian life, and to help them articulate and understand their experiences through the communal process of making theatre. By rehearsing and performing scenes from Shakespeare's plays, as well as the writings of our veterans, we believe we are making a contribution to building a better community in the face of an increasingly solipsistic world. Rather than further justify or explain our program using my own words, here is a monologue from our own Lou Bullock. The Flu Shot by Lou Bullock Thirteen years ago I was diagnosed with prostate cancer. It's not a discouraging problem in these days of medical technology, so I marched myself over to Sloan Kettering where I underwent radiation therapy for 40 days. About four weeks into my therapy the oncologist called me in and told me that the radiation treatment was compromising my bone marrow and that it was imperative that I get a flu shot. He told me that for some reason the shots were difficult to get that year, and though Sloan had the vaccine they preferred to save it for those patients who needed it most. So I marched off to my internist who told me he did not have any vaccine either. And so it went with all my medical contacts. A friend then told me that the VA had the vaccine. So I marched off to the VA where a heavy lady with a lot of gold jewelry interviewed me. I told my story: I didn't need VA care, just a flu shot. She took my history and financial status and then left the room. When she returned she simply said that her superiors had reviewed my case and that it was determined that I could financially take care of myself. And then she said, "Medically you do not have a respiratory problem or an immune deficiency disease. You only have cancer. So we cannot give you a flu shot." I don't remember what happened after that. I was stunned, I guess. Fortunately, the story has a happy ending: I got my flu shot through my labor union. I finished therapy and got on with my life. But that statement "You only have cancer" ate at me. Look, I've heard a lot more distressing VA experiences here at Bedlam Outreach. But my experience made me think of how little my country appreciated my service. I was drafted just out of school. I spent two years in a foreign country. How much were those two years worth to my country? Flu shots cost ... what? $20? So that's 10 bucks for each year spent overseas. And that is what my country thought of my service. I got on with my life. But it continued to eat at me. Now, this is what brings me to Bedlam Outreach. When strangers visit our open house nights, I'm sure they wonder what we do here, and why we study Shakespeare. In our reading of Much Ado About Nothing, one of the characters asked of a battle, "How many gentlemen have you lost in this action?" The answer was "But few of any sort, and none of name." Our stalwart leader explained to us that this was how most casualties were related in Shakespeare. The nobles might be listed: the Duke of Essex, the son of the earl of Hereford, etc. and then: "The rest of no name." I began to think. All through American history American military men have had distinctive names. The Minute Men or the Green Mountain Boys in the Revolution. Johnny Reb in the Civil War. In the First World War we were the doughboys or the Yanks. And in the Second World War, of course, GI Joe. Even our enemies had names: the red coats, the Jerries. But since World War II, and after several wars that no one can explain (or even remember), we really have not had a name. We were "our men and women in the service." No name. Well, in the parlance of our elected and appointed officials, perhaps we do have a name: We are now "boots on the ground." Boots on the ground. Boots. A name you call your cat. No: An inanimate object. In today's world if you have a hole in that boot, you don't even repair it. You throw it away. That's why we come to Bedlam Outreach. It's a place where we have a name. And it's a name given us by Shakespeare. He spoke of soldiers as a "band of brothers." And that's what we are. A band of brothers and–in today's world–a band of brothers and sisters. A group of men and women with a common life experience. Not a unique experience, but a shared one which bonds us. We have a place where we have each other's back, where we can talk, and laugh, and bare our wounds, both physical and psychic in a ritual of love, knowing that we have never ending support from our brothers and sisters. And at Bedlam Outreach all this inspired by a dramatist/poet who lived 400 years ago. A man who included soldiers in almost all of his plays. A man who loved and laughed at our foibles, and who honored our service and our bravery. So here's to you, late of no name, and now my band of brothers and sisters: I thank you for being here for me, and I salute you. Thanks to the incredible talents of the Rutgers Mason Gross third-year acting company, my new play "Bride of the Gulf" is going up at Manhattan Rep. Bride of the Gulf represents a reworking of the "Brides Look Forward" play I wrote for the Basra to Boston project at Fort Pointe Theatre Channel. Bride of the Gulf is a new play that tackles the normality of war in Basra, Iraq through the deep, yet hostile relationship between a widow and her mother-in-law. Set amid the violence that engulfed Southern Iraq after the British withdrawal of 2007, a sharp-witted Iraqi woman goes in search of her missing husband at the behest of her mother-in-law. When creating the play for the Basra to Boston project, we drew on transnational conversations that took place throughout 2016, as well as the playwright's memories of Iraq in 2007.  The other night I had the chance to catch Thomas Ostermeier's German adaptation of Shakespeare's Richard III at the Barbican in London. An actor friend from Korea (and studying at Rutgers) caught the play in Berlin, and strongly recommended the production on the basis of the performance of the lead actor, Lars Eidinger. I had never visited the Barbican before, and I have to admit that visiting the complex was half the attraction. I wanted to see the venue, which I had trouble imagining, where the Royal Shakespeare Company regularly performed in London in the time of Peter Hall and Trevor Nunn. I had passed near the tower flats before, which from the outside streets appeared a half abandoned slum. As it turned out, the Barbican was beautiful. It appears, from within, more like an urban shelter of gardens, blue London winter light, and homes politely perched atop each other to allow for more public space. And the massive arts complex feels like a neighborhood version of the South Bank theatres, cinemas, and museums. Visiting the Barbican for the first time, and being aware that Antony Sher had performed Richard III in that space with his remarkable spider-like sketches of the king, probably framed Thomas Ostermeier's Richard III for me. It also helped that I grabbed a front row ticket for sixteen pounds. Supposedly, the view was "obstructed" because the subtitles were at an angle, but I could read them perfectly well. [Those kind of London deals are an important part of what make the city a superior theatre town to New York.] Ostermeier's Richard III played like a tennis match between Shakespeare and modern politics, each working together, and against each other. It was beautiful. Michael Billington claimed that Ostermeier's production had stripped the play of its politics. I strongly disagree, and wrote a lengthy comment about this on the Guardian's website. I admire Michael Billington very much--I just felt that he got this one wrong. I thought I should go ahead and repost my response here on this website. What else is it for? Here's the link to the comment: https://discussion.theguardian.com/comment-permalink/93476727 And here's the text of the comment: I found Thomas Ostermeier's production at the Barbican deeply political, and its contemporary relevance moved me greatly. I felt that Ostermeier underlined two aspects of modern politics. The first was a fearful and dangerous acquiescence to authoritarianism on the part political elites like Hastings and Buckingham, an acquiescence which we now see in the faces of operatives like Reince Priebus (former chair of GOP and now Trump's chief of staff), and perhaps even the MPs lining up to obediently bleat their way to Brexit. To name a striking instance, the actor playing Buckingham, as he shuffled Dorset and Rivers off to their deaths, momentarily lost his nerve, turned white as a ghost, gripped the railing, and looked guiltily back at the audience: it was a brave and novel performance, rocking between private doubts and public sycophancy. Another remarkable moment: The Hastings scenes, stripped of most of the weak lines about an incident of medieval adultery, focus solely on Hastings' commitment to institutions, and the vanity with which he crows against his opponents. In the case of Hastings, the institution he naively focuses on is the lineal inheritance of the crown. In the case of David Cameron, it was the sloppy outcome of an unprecedented (and disastrously planned) popular vote. Maintaining institutions takes a lot of hard work, and we continually see leaders fail to do the necessary groundwork needed to defend our liberal institutions against right-wing power grabs. The second major theme I saw in Ostermeier's production was the solipsism of political leaders like Margaret of Anjou, Edward IV, Richard III, and Donald Trump. These are people that cannot understand politics except in terms of how it affects their own ego and sense of self. There is a disturbing tendency among the electorate to mistake emotional, shameless, "honest" speaking for political truth and effectiveness. I saw this reflected in Richard's "baring all" seduction of Lady Anne, as well as Richard's willingness to throw (somewhat effective) tantrums, cowing his followers into obedience. Another consequence of solipsistic leaders like Shakespeare's Richard III is that they may fail to recognize when their methods stop working. After his dismissal of Buckingham, Richard III smears white cream across his face, creating a wrinkle-free version of himself. He resembles the doll-like children he had murdered moments before. And then he tries the exact same trick of seduction that he used on Lady Anne with the bereaved Queen Elizabeth, only he fails to realize that eventually the charm wears off. I imagine Boris Johnson felt a bit like that after his Brexit "victory," as the premiership slipped away from him. I also imagine that Donald Trump will feel that way some time after he drags the United States into another unwinnable war, and his presidency finally sputters to a halt. The dangerous charismatic politics of today no longer mimic the fascist political behavior of the Second World War. Dressing up the actors in fascist uniforms made for a useful reading of the 20th century, but not necessarily the 21st. Mr. Billington is correct: it would be inexcusable, given where we stand in 2017, to perform one of Shakespeare's history plays and strip it of historical relevance, but that is not what has happened here, even if the emphasis on moral cowardice, sycophancy, and solipsism diminished the play as a specific metaphor for a certain type of fascism. But I think Ostermeier's version was more realistic: it doesn't take a handful of evil geniuses, it just takes several hundred fools and an egoist with charisma. Quite a few critics described this production as a wild reimaging of the play. I don't agree with that at all. The first two-thirds are quite conservative, and retain many scenes and moments that most directors choose to excise. Taken all together, the cuts, amendments, and adjustments to the text were no more present here than what we have found elsewhere.

Shakespeare proves the best playwright in town nine times out of ten, not just because of his creative invention with the English language, but because his plays inspire living artists to push themselves to new imaginative heights: to riff of previous interpretations, to shake us with modern political concerns, to tweak line readings, to shake off the past and tell the story as if it has never been told before. His flexibility with form and content is part of his appeal. I think that someday Americans may begin to look at Eugene O'Neill in a similar way, if we are afforded the opportunity to experience more of his work on a regular basis. But for now, there is only Shakespeare, and perhaps Homer for the tweedier set. |

AuthorJ. M. Meyer is a playwright and social scientist studying at the University of Texas at Austin. Archives

July 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed