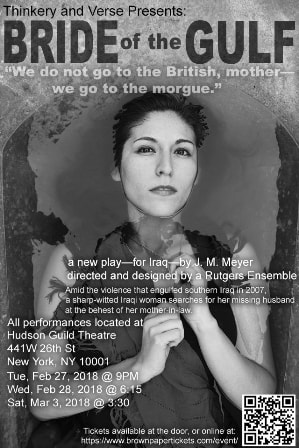

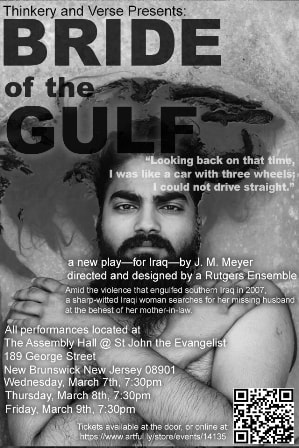

| Bride of the Gulf will preview for a limited run of six performances in New York and New Jersey in the spring of 2018. The first three shows will occur in Manhattan on: Tuesday, February 27th, 9pm Wednesday, February 28th, 6:15pm Saturday, March 3rd, 3:30pm These three performances will be a part of Winterfest @ Hudson Guild Theatre, 441W 26th St, New York, NY 10001. The play will then preview in New Brunswick, New Jersey at the Assembly Hall of St. John the Evangelist, 189 George Street, New Brunswick, New Jersey. The New Brunswick shows will occur on: Wednesday, March 7th, 7:30pm Thursday, March 8th, 7:30pm Friday, March 9th, 7:30pm Tickets are now available through Artful.ly ticketing services. In August 2018, Thinker & Verse plans to bring "Bride of the Gulf" to the Edinburgh Fringe for its international debut. |

|

0 Comments

Hi Johnny,

My name is C. Stephenson--I met you briefly during one of your visits to Lawrence. Anyway, I am the dramaturg for the B'srd Shrts and I am currently compiling playwright bio's for the program, and we thought it would be kind of snarky to do an interview format for your bio, since you are alive. (Also, I know Churchill is alive... but I can only manage so much :]) If that is okay with you, I was wondering if an e-mail format for the interview would be okay, as I'm not sure I could set up a phone interview quickly enough. If so, let me know and I'll e-mail you back a document with the questions that you can fill in. Also please feel free to add anything pertaining to yourself as a playwright or simply as a person that you would like to be included. I have a small bio from Kathy and Tim I've looked at so hopefully I'll be able to cover a good amount. Thanks, C. Stephenson --------------------------------------------------------------------- Hi C., Why don't you fire away, and we'll see how it goes? J. M. --------------------------------------------------------------------- Thanks for the quick response. Alright, firing away: Q: Okay, I have to ask the typical protocol bio question of: Where were you born, when were you born, where did you grow up and does that or your family have any influence on your writing/authorship? Q: Favorite playwright? Favorite absurdist playwright? Q: What style is your typical go to style for playwrighting, or do you take the Churchill/Beckett “can’t categorize me” approach? Q: Thanks for serving in the military— I have the utmost respect for you, I come from a long line of servicemen. How much does that influence or seep into your dialogue/themes? I can’t imagine a life experience at that caliber not finding its way into your art in some way. I am a new mom and I find even when I try not too, essences of that find their way into my scripts. Q: What’s your biggest pet peeve in life or as an artist? Q: Would you rather go to lunch with Samuel Beckett or Artaud? Care to explain? I think each would provide polarizing opposite effects. Q: Can you give a little overview of your process and approach to Cryptomnesia, or would that be a disservice to the show itself? Was there an object, idea, movement, etc. that influenced the creation? Q: Do you have a hidden talent? Q: If you could trade places with any person in history, dead or alive, who would it be? Such a lame question, but I think it says a lot. Q: Anything else you’d like to share? Thanks for baring with my horribly cliche questions, I didn't have adequate time to prepare a nice thoroughly thought out interview. I'll conduct a better one if you're around during production--keep it in the dramaturgy notebook. Thanks, C. Stephenson --------------------------------------------------------------------- Q: Okay, I have to ask the typical protocol bio question of: Where were you born, when were you born, where did you grow up and does that or your family have any influence on your writing/authorship? I was born in Dallas, Texas in 1982. I grew up in Dallas, New Orleans, and Kansas City. I am sure that my childhood shapes my plays. I am the oldest child in a family with three sons and three daughters. My parents are Roman Catholic, or at least what passes for Roman Catholicism in the United States. Social context and family play decisive roles in shaping who we are, but writing is more specific than living because with writing we can edit, revise, and manufacture our wares. A short play like Cryptomnesia can only share the smallest fraction of common ground with its playwright. Q: Favorite playwright? Favorite absurdist playwright? My favorite playwright, the playwright I spend the most time with, is Shakespeare. The tag 'absurdist' is more useful for audience members and critics than it is for the playwright or other artists; it helps audience members approach a piece with a certain wariness, and perhaps an openness to incredulity. One of my other favorite playwrights is Christopher Marlowe, Shakespeare's contemporary and stylistic predecessor; I suppose I adopt an 'absurdist' framework when watching his plays, which I usually enjoy. Of the twentieth century playwrights, the works of Samuel Beckett remain the most accessible thanks to the 'Beckett on Film' series. But if I have a preference for Beckett over, say, Churchill or Albee, that probably has more to do with convenience and accessibility than it does with aesthetics. Q: What style is your typical go to style for playwrighting, or do you take the Churchill/Beckett “can’t categorize me” approach? Do they say that? Or, from a creative place, do they simply find 'style' unhelpful? If Churchill labeled herself 'absurdist,' she might not have written plays like Top Girls or Serious Money. Q: Thanks for serving in the military— I have the utmost respect for you, I come from a long line of servicemen. How much does that influence or seep into your dialogue/themes? I can’t imagine a life experience at that caliber not finding its way into your art in some way. I am a new mom and I find even when I try not to, essences of that find their way into my scripts. What I saw and did in Iraq and Afghanistan alienated me from America. I mourn the disconnect between what we are, and what we could have been. I am very lucky, in that I have travelled through most of America, and much of the world, and have had the chance to respond to it. But when it comes to absurdism, I think it is more helpful to ask audience members, 'How do your own personal experiences shape your reaction what you are watching, listening, and feeling?' The playwright must be a little hands off; what we're making in Cryptomnesia is aesthetically closer to a mirror than to autobiography. It's not a landscape, or a character sketch, or a history. The fact that human beings are capable of observing absurdist theater and responding to it intelligently is almost a miracle. But however they respond to it, that response probably has more to do with who they are and where they are from than anything else. The artists and the playwright anticipate the audience, but cannot lead them with a hook or tether. Q: What’s your biggest pet peeve in life or as an artist? Distracted acting. Waiting for laughs. Carelessness with handguns. The incessant meowing of cats. Q: Would you rather go to lunch with Samuel Beckett or Artaud? Care to explain? I think each would provide polarizing opposite effects. Artaud has been dead much longer, and I think his advanced decomposition would be least likely to spoil my lunch. Q: Can you give a little overview of your process and approach to Cryptomnesia, or would that be a disservice to the show itself? Was there an object, idea, movement, etc. that influenced the creation? When Tim commissioned the play, he asked me to think about what 'absurdism' might mean to students at Lawrence University. Last fall, I had the chance to survey the campus, sit in on classes, and meet the students. I also explored the university's past, and tried to understand what it looked like to the people in the present. And, truth be told, I found I really liked Lawrence University. I had never been to a liberal arts college. I enjoyed the experience, and enjoyed observing what appeared to be the experience of the students and the professors. If absurdism involves some kind of confrontation with society--and I think it does--then my liking Lawrence presented a weird sort of dramaturgical problem. It took some work to get around that. Given the absence of obvious targets, I took a look at the individual 'person' who happens to be at Lawrence, and what they look like in the wider, less comforting society. Eventually I wound up with an observation, and two questions: As strong the local society might be, the individual is not necessarily able to remain in such a comfortable place. What might take them out of that society, and what are the personal costs thereof? That was the starting point. The starting point was a sort of complete McMansion; the next step was to destroy the roof, and tear out the drywall, and find out if anything was alive beneath the carpeting and inside the frame of the house. Q: Anything else you’d like to share? Yes, I suppose I would like to offer a few words about the other playwrights, and where I feel absurdism comes from. A popular definition of 'absurd' proposes 'crazy, unreasonable, untimely' as a suitable meaning for the word. The aesthetics of absurdism suggest mystery, confusion, and perhaps 'cutting-edge' theatrics, but the artists associated with absurdism spend an awful lot of its time looking mournfully backwards. Antonin Artaud named his theater after a French playwright of the previous generation (Alfred Jarry), and Artaud harvests his damaged characters from deep in the European past. Samuel Beckett pulls many of his images from the devastated landscapes of the Second World War, and his characters incessantly attempt to remember--remember what? a story? a person? How exactly did they tumble into their current situation? How can they get it right? How can they do it better next time? Whereas Artaud offers visual ecstasy and religious voyeurism, Beckett offers comic circles and tragic cynicism. As a whole, the plays of Caryl Churchill defy any particular emotional landscape, through she also looks backwards towards realism and naturalism. Her play This is a Chair seems to reference the late twenties French painting called La trahison des images. The painting shows us a pipe, but is helpfully labeled, Ceci n'est pas une pipe: "This is not a pipe." And of course the label on the painting is correct; it is not a pipe, but rather a painting. But This is a Chair. Churchill explores the spongy limits of realism, the darkness that surrounds the everyday people that democratic-capitalism panders to. The three writers--Artaud, Beckett, Churchill--find themselves in a crazy, unreasonable, untimely moment. Whatever it is that they were looking for in their youths, it was not quite there, and the experience of its absence granted no secret wisdom that can help the next generation do any better. Comic circles, tragic cynicism. Realism with spongy limits. Visual ecstasy and religious voyeurism. The techniques and mysteries of these writers trace back to the witches of Macbeth, Shakespeare's soliloquies, and the clipped in media res epics of Homer. But while these writers are decidedly Western in thought and action, one can also look further afield in the wide world and find theatrical art with a kindred spirit; the rhythmic mysteries of Noh drama come to mind, where the key 'event' of the play can involve an act listening, rather than an act of confrontation. There are others as well, but that's enough out of me. Thanks to the incredible talents of the Rutgers Mason Gross third-year acting company, my new play "Bride of the Gulf" is going up at Manhattan Rep. Bride of the Gulf represents a reworking of the "Brides Look Forward" play I wrote for the Basra to Boston project at Fort Pointe Theatre Channel. Bride of the Gulf is a new play that tackles the normality of war in Basra, Iraq through the deep, yet hostile relationship between a widow and her mother-in-law. Set amid the violence that engulfed Southern Iraq after the British withdrawal of 2007, a sharp-witted Iraqi woman goes in search of her missing husband at the behest of her mother-in-law. When creating the play for the Basra to Boston project, we drew on transnational conversations that took place throughout 2016, as well as the playwright's memories of Iraq in 2007.  The other night I had the chance to catch Thomas Ostermeier's German adaptation of Shakespeare's Richard III at the Barbican in London. An actor friend from Korea (and studying at Rutgers) caught the play in Berlin, and strongly recommended the production on the basis of the performance of the lead actor, Lars Eidinger. I had never visited the Barbican before, and I have to admit that visiting the complex was half the attraction. I wanted to see the venue, which I had trouble imagining, where the Royal Shakespeare Company regularly performed in London in the time of Peter Hall and Trevor Nunn. I had passed near the tower flats before, which from the outside streets appeared a half abandoned slum. As it turned out, the Barbican was beautiful. It appears, from within, more like an urban shelter of gardens, blue London winter light, and homes politely perched atop each other to allow for more public space. And the massive arts complex feels like a neighborhood version of the South Bank theatres, cinemas, and museums. Visiting the Barbican for the first time, and being aware that Antony Sher had performed Richard III in that space with his remarkable spider-like sketches of the king, probably framed Thomas Ostermeier's Richard III for me. It also helped that I grabbed a front row ticket for sixteen pounds. Supposedly, the view was "obstructed" because the subtitles were at an angle, but I could read them perfectly well. [Those kind of London deals are an important part of what make the city a superior theatre town to New York.] Ostermeier's Richard III played like a tennis match between Shakespeare and modern politics, each working together, and against each other. It was beautiful. Michael Billington claimed that Ostermeier's production had stripped the play of its politics. I strongly disagree, and wrote a lengthy comment about this on the Guardian's website. I admire Michael Billington very much--I just felt that he got this one wrong. I thought I should go ahead and repost my response here on this website. What else is it for? Here's the link to the comment: https://discussion.theguardian.com/comment-permalink/93476727 And here's the text of the comment: I found Thomas Ostermeier's production at the Barbican deeply political, and its contemporary relevance moved me greatly. I felt that Ostermeier underlined two aspects of modern politics. The first was a fearful and dangerous acquiescence to authoritarianism on the part political elites like Hastings and Buckingham, an acquiescence which we now see in the faces of operatives like Reince Priebus (former chair of GOP and now Trump's chief of staff), and perhaps even the MPs lining up to obediently bleat their way to Brexit. To name a striking instance, the actor playing Buckingham, as he shuffled Dorset and Rivers off to their deaths, momentarily lost his nerve, turned white as a ghost, gripped the railing, and looked guiltily back at the audience: it was a brave and novel performance, rocking between private doubts and public sycophancy. Another remarkable moment: The Hastings scenes, stripped of most of the weak lines about an incident of medieval adultery, focus solely on Hastings' commitment to institutions, and the vanity with which he crows against his opponents. In the case of Hastings, the institution he naively focuses on is the lineal inheritance of the crown. In the case of David Cameron, it was the sloppy outcome of an unprecedented (and disastrously planned) popular vote. Maintaining institutions takes a lot of hard work, and we continually see leaders fail to do the necessary groundwork needed to defend our liberal institutions against right-wing power grabs. The second major theme I saw in Ostermeier's production was the solipsism of political leaders like Margaret of Anjou, Edward IV, Richard III, and Donald Trump. These are people that cannot understand politics except in terms of how it affects their own ego and sense of self. There is a disturbing tendency among the electorate to mistake emotional, shameless, "honest" speaking for political truth and effectiveness. I saw this reflected in Richard's "baring all" seduction of Lady Anne, as well as Richard's willingness to throw (somewhat effective) tantrums, cowing his followers into obedience. Another consequence of solipsistic leaders like Shakespeare's Richard III is that they may fail to recognize when their methods stop working. After his dismissal of Buckingham, Richard III smears white cream across his face, creating a wrinkle-free version of himself. He resembles the doll-like children he had murdered moments before. And then he tries the exact same trick of seduction that he used on Lady Anne with the bereaved Queen Elizabeth, only he fails to realize that eventually the charm wears off. I imagine Boris Johnson felt a bit like that after his Brexit "victory," as the premiership slipped away from him. I also imagine that Donald Trump will feel that way some time after he drags the United States into another unwinnable war, and his presidency finally sputters to a halt. The dangerous charismatic politics of today no longer mimic the fascist political behavior of the Second World War. Dressing up the actors in fascist uniforms made for a useful reading of the 20th century, but not necessarily the 21st. Mr. Billington is correct: it would be inexcusable, given where we stand in 2017, to perform one of Shakespeare's history plays and strip it of historical relevance, but that is not what has happened here, even if the emphasis on moral cowardice, sycophancy, and solipsism diminished the play as a specific metaphor for a certain type of fascism. But I think Ostermeier's version was more realistic: it doesn't take a handful of evil geniuses, it just takes several hundred fools and an egoist with charisma. Quite a few critics described this production as a wild reimaging of the play. I don't agree with that at all. The first two-thirds are quite conservative, and retain many scenes and moments that most directors choose to excise. Taken all together, the cuts, amendments, and adjustments to the text were no more present here than what we have found elsewhere.

Shakespeare proves the best playwright in town nine times out of ten, not just because of his creative invention with the English language, but because his plays inspire living artists to push themselves to new imaginative heights: to riff of previous interpretations, to shake us with modern political concerns, to tweak line readings, to shake off the past and tell the story as if it has never been told before. His flexibility with form and content is part of his appeal. I think that someday Americans may begin to look at Eugene O'Neill in a similar way, if we are afforded the opportunity to experience more of his work on a regular basis. But for now, there is only Shakespeare, and perhaps Homer for the tweedier set. 'Last Saturday, the Fort Point Theatre Channel artistic collective produced my play, Brides Look Forward, alongside Amy Merrill's absurdist drama In the Reeds.

The plays were of wildly different styles, but I don't think Amy and I could have been more pleased with the results: it was an engaging, interdisciplinary evening of performances, with live music, sounds streamed in from Iraq, and poetry in both English and Arabic. You have one more chance to catch the Basra-Boston pieces as a collective: Friday, November 4, 2016, 8 pm, at the Arts at the Armory, 191 Highland Avenue, Somerville, Massachusetts. In response to reading on October 1st, I have 'adjusted' my play a bit. Many thanks to the excellent Kathryn Howell, who has cast and directed the piece each step of the away! Fort Point Theatre Channel's Marc Miller has done most of the hard labour of producing the show thus far--I do not think this project could have happened without his help, and I deeply appreciate his kindness and hospitality. Do you remember the board game "Chutes and Ladders," where players take turns climbing the rungs of a ladder, only to slide back to square one over and over again? The makers of the game illustrated the board with children who, for good behavior, were shown climbing the ladder, and for bad behavior were sent sliding down the chutes. KILL FLOOR, the new play that just went up at LTC3, depicts modern poverty, where the ladders are missing the lower rungs, and the gleaming steel chutes of modern America provide the blind and driving illusion of progress all the way back to square one.

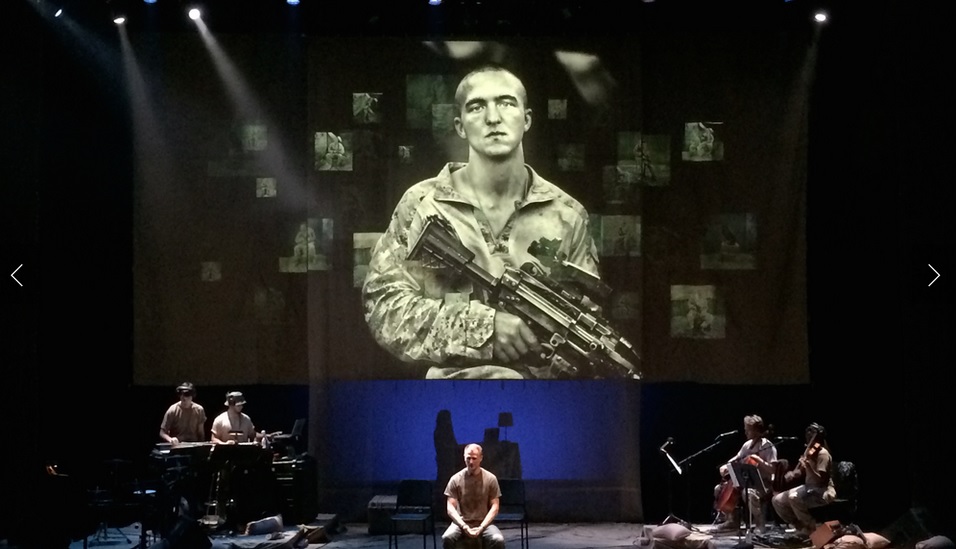

Marin Ireland delivers a star turn as 'Andy,' a newly released ex-convict. Desperate for a job, she signs on as slaughter-house employee, where she's quickly sent to the kill floor. Every thirteen seconds a bolt gun kills a cow, while another machine lifts the fresh carcass out of the pen and skins it--sometimes while the animal is not quite dead. Accidents are common, sometimes leading to more pain for the cattle, and sometimes injuries for the workers. The kill floor itself is kept just beyond our sight, but its implications bleed out into every aspect of Andy's life. Rick, Andy's affably manipulative and dangerously amorous boss (played by Danny McCarthy), tells her not to worry: her co-workers are Mexicans ("good workers...reliable") but because his bosses are "racist as hell," she's likely to get promoted above them and sent upstairs to do office work. As the Bard says, "All [wo]men have some hope," and some hopes are higher than others. Andy's desperation to find a job is rooted in her desire to provide for her biracial teenaged son, B, who is simply embarrassed by Andy's reemergence. B is understandably more interested in surviving high school and first-crushes than he is in bringing his estranged and needy mother back into his life. B remembers too well his mother's arrest, and Marin Ireland provides subtle, nervous gestures that suggest that Andy is still struggling with past addictions, though she insists otherwise to her boss. Instead of loving his mother, B reaches out to Simon, a white schoolmate and self-fashioned rapper. Simone lays out "sick rhymes" for the benefit of B. B helps Simon score weed. More importantly, the two are caught in an unequal and entirely believable sexual awakening. 'Coming out,' which is getting easier in much of America, seems a nihilistic social choice in their world, and their relationship stands tensely at the edge of discovery. The two young performers, Nicholas L. Ashe and Samuel H. Levine, fully own their characters; under the guidance of director Lila Neugebauer, they create the play's most dynamic, topsy-turvy moments; even if Koogler's insights on race, sexuality, and high school politics are not radically fresh, they are truthfully delivered with wit, grace, and daring. With B avoiding her, Andy hesitatingly looks for connection elsewhere. She first turns to Sarah (played by Natalie Gold), an outgoing woman from the right-side of the tracks; the relationship allows the play to show that the two women face similar emotional trials, but with such wildly different economic resources as to not be speaking the same language. Sarah thrives (and perhaps even applauds herself) for keeping Andy company, but Andy is unwilling or unable to broach her own past, and so their friendship is stunted. As that relationship stalls, Andy takes a turn into another dead-end by consenting to her married boss' request for a date. Abe Koogler, showing his chops for modern drama, begins many of his quick, short scenes in media res, with the relationships already established and understood by the characters, and the drama centered on each person's peculiar verbal strategies as they drive after their meager, vulnerable (and often funny) desires. He expertly writes in the staccato semi-fluency that thrives in America's small black box theaters. (Why, in American dramas about the economically disadvantaged, is there a shortage of eloquent, rhetorically powerful people saying stupid things? It must be a two-hundred year carryover from the imprinting excellence of Charles Dickens. But Mark Twain is our man, and he had plenty of characters who earnestly believed in the tomato paste they were selling.) At any rate, as with David Mamet and Annie Baker, each broken and partial sentence leaves room for our sympathies. The less the characters say, the more we root for them; the more they open their mouths, the more we know they lack the resources to thrive, and dash the hopes we have invented for them in their quiet moments. The set by Daniel Zimmerman (wide, shallow, and grey) works with Ben Stanton's lighting and Brandon Wolcott's sound to deliver the audience into an icy world where a slaughterhouse and budget apartment share the same colorless walls. Prison and slaughter are never seen, but always present. The actors dart in and out of the wings like cattle through chutes, and neither they nor we have much idea of what's coming next. The simplicity of the design invited the imagination into the world of the play, and ties together the disparate threads of the story, so that the voices and themes from one scene echo into the next. It is a play that disposes with an obvious ending, or a well-made play's denouement. Unlike in Annie Baker's THE FLICK (or Oscar Wilde's THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING ERNEST), there are no craftily hidden pieces of paper that cause the play to burst into a climax and a resolution. Most of Koogler's characters could struggle on, nearly unchanging, and constantly caught off-guard, for years and years. Rather than forcing a neat cap on the play's final moments, Koogler brings it to a close at the ninety minute mark, like the closing shift in a warehouse; the lights silently dim on an evening of open, honest, and throat-catching performances. KILL FLOOR depicts characters living in poverty; they prove likable, but they will not win. This play is a necessary stab in the eye to the Group Theatre's optimism at the end of the Great Depression. If the playwright senses hope, but sees little way out, then we should take his word for it, and thank him for his honesty: we should not request that playwrights invent neat little plots designed to satisfy our complacency.  A scene from BASETRACK LIVE, a theater project that slices live performance with visceral footage of the war in Afghanistan, quiet conversations with military wives, and a powerful musical score. [Image taken from the BASETRACK LIVE website.] A scene from BASETRACK LIVE, a theater project that slices live performance with visceral footage of the war in Afghanistan, quiet conversations with military wives, and a powerful musical score. [Image taken from the BASETRACK LIVE website.] MCCULLOUGH THEATRE, TEXAS PERFORMING ARTS CENTER, AUSTIN, TEXAS: Three years ago, Texas Performing Arts Center (TPAC) brought us BLACKWATCH, a stage-play that explored how the history of the famous Blackwatch Royal Highland Regiment unfolded in the killing fields of modern Iraq, and how that history ultimately came to an due to a bureaucratic cost-cutting decision back in London. The show proved spectacular, and brought big-city virtuosity to Austin. Texas Performing Arts has now followed up on that success with the outstanding debut of BASETRACK LIVE, produced by Anne Hamburger and En Garde Arts. Created by Edward Bilous, directed by Seth Bockley and adapted by Jason Grote, this new play combines battlefield journalism, live performance, and disturbing interviews, and then exposes and explores the strange deprivations, honors, and hopes of the 1-8 Marines, a unit that has deployed and redeployed (time and again) since 2001. The play opens with short snippets of interviews with Marines in Afghanistan in the year 2010; each Marine says his name and names his home, and then his image falls into the distance and another Marine takes his place. Their voices rumble together (a cacophony of youth) as the onstage band, a four person unit, suddenly displaces the remaining silence of the auditorium; the music, directed by Michelle DiBucci, grants the multimedia images a sense of enduring strength. The exact mission in Afghanistan remains vague and purposeless, but the band's presence underlines the intention of the play: to honor the experience and challenges of the men and women serving in today's armed forces, often in wars that began just a few years after those men and women were born. The multimedia interviews slice back onto the stage, and introduce a new theme: the intentions of 'the few and the proud' who choose to become Marines. The interviews then give way to a live performer, Tyler La Marr, who portrays AJ, a Marine corporal that seeks to explain his own decision to join the Marine Corps, as well as his decision to become an infantryman, and his day to day experience of life in Afghanistan. The actor Ashley Bloom then enters the stage-light. She portrays AJ's wife, Melissa. Her face appears as a projected image in the heights above the stage. She tells her story to the camera of a laptop computer. A gauze curtain divides Melissa and AJ, just as the script divides their stories; AJ talks exclusively of war, while Melissa talks of AJ and the experience of his presence and absence in her own life. AJ mourns the death of a friend, while Melissa fears a knock on the door that may announce her husband's own violent death. AJ describes firefights and Oakley sunglasses, while Melissa describes giving birth to their only daughter. Painfully, AJ never mentions his wife, while Melissa's every word centers around her husband. A bullet puts an end to AJ's deployment, as it rips through his bicep and sends him home; the journey ends in a matter of days. Suddenly estranged from his unit, he disparages (and disdains) his estrangement from his wife. He seems to miss Afghanistan more than he ever missed her. Melissa recoils from AJ's violent outbursts, his drinking, and his destructive obsessions with handguns and rifles. The Marine Corps ends AJ's young career with a medical discharge; he carries with him memories of a painful past, an uncertain present, and a future with little hope. Melissa and AJ attempt couples' counseling, but it fails; the once happy couple can remember all the reasons that they hate each other, but not the source of their love. Melissa eventually leaves AJ. AJ finally drags himself to therapy for PTSD. The play concludes with hope, as the therapist tells AJ that "the hard part...is over, as of right now." BASETRACK is a superior example of 'verbatim' theater, wherein the artists lift the script from interviews conducted with real people. In this case, the real people are combat veterans from 1-8 Marines, a unit deployed to Afghanistan in 2010, and their wives. The show smartly centers on AJ, with a small cast of video interviews orbiting his experience. AJ works as a main character because he is smart enough to laugh at his own foibles, and honest enough to detail the challenges he has faced. The peculiar brilliance of the show stems from intersection (or lack thereof) between the narratives of AJ and Melissa. The script highlights the awful distance between spouses during a military deployment, especially for the very young. And so the play universalizes the story of AJ and Melissa by tracing the similarities between their experiences and those of their peers; BASETRACK LIVE presents a sort of multimedia triptych of live performance, music, and viscerally assembled videos and photographs. (The video designers were Sarah Outhwaite and Esteban Uribe. Their work represented the best use of video I have seen in Europe or America.) The voices of the women prove especially important. The play presents clips of interviews taken from Skype or Google Chat. Each woman, painfully young, describes the experience of waiting, day after day, for news both good and bad about their spouses deployed to Afghanistan; unfortunately, the journey of these young women does not get easier upon the unit's return. Medi, one of the wives, dances around the challenges she has faced: "You really have to be careful of what you say and how you present things. You know, like I said...[their] innocence is gone....Their whole way of thinking is completely different over there. That just affects how they respond to you when they come home." One of the limitations to verbatim theater is that it can only use the language that comes up in the interviews. If the interviewed veterans and wives avoid certain topics or perspectives, then the show must necessarily also avoid those topics. Verbatim theater holds a mirror up to nature, but cannot completely control the quality of the nature that enters its frame; just as the academic disciplines of ethnography and political theory often stress different dimensions of the same problems, so verbatim theater and 'regular' theater differ in their outcomes, though not necessarily in effectiveness. The use of multimedia and music helps BASETRACK LIVE overcome the limitations of verbatim theater, as these cinematic elements transform everyday language into poetry through the use of echo, repetition, and underlined sound. The band, which consists of the outstanding quartet of Trevor Extor, Kenneth Rodriguez, Mazz Swift, and Daniele Cavalca, elevates the play with relentless intensity--Schiller and Goethe would be pleased. If there is room for refinement, it might lie in the combat scene. AJ, the lead character, remembers a sudden unleashing of 'chaos.' But an American infantrymen, when pressed, can reveal a precision to a combat that consists of casualty reports, air support, covering fire, and fire commands, the sum of which grants combat the frightening (yet empowering) quality of a testosterone and adrenaline riddled blood-sport. This 'precision' in midst of seeming 'chaos' helps explain the willingness of soldiers to return to the fire time and time again. American soldiers, backed with taxpayer equipment, feel that they can win any firefight they stumble into (more often than not). And so the combat scene could use further exploration (but not too much). In regards to content, the play might also consider pointing out that an American soldier's pay increases dramatically when stationed overseas, thus enabling the purchase of expensive Oakley's, new pickup trucks, new tattoos, and guns, guns, guns once a soldier returns home. There are a also a few moments of humor that may require a little more direction in order to cue the audience that laughter is acceptable in a war story. But my complaints are mild, and my praise is strong. BASETRACK LIVE provides an intelligent, graceful way to empathize with the twenty-first century military experience. For a veteran like myself, it brought back surprising memories and shadows. It is a painful, sad place to go. The passages in which the soldiers contemplate suicide are particularly haunting, and open doors I prefer to keep locked and closed. But it is worth opening those doors to remind oneself that the war in Afghanistan, though perpetually 'winding down,' continues instead with perpetual cost. As it was in 2001, so it continued in 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, and 2014. The BASETRACK LIVE project must continue. One hopes the creative team might consider asking the Afghans, who have now fought against (and alongside) the Americans for thirteen years, what they think of us. With the exception of Hamid Karzai, it often feels that we have thought painfully little of them. BASETRACK LIVE shows us a video in which an Afghan woman screams at the presence of a video camera in her family home; I walked away from BASETRACK without much of an understanding of her pain, but that seems fitting in a portrait that emphasizes the 1-8 Marines and the struggles they face within their own homes upon returning from combat. The play is now on tour. Seek it out. In collaboration with Humanities Texas and Chess Theatre Company, I am presenting George Farquhar's THE RECRUITING OFFICER as a part of the Veterans' Voices play series. Isto Barton will be directing a select group of am-dram performers in a two hour celebration of Farquhar's comic masterpiece--a play that smiles at the occasionally crooked relationship between soldiers and society.

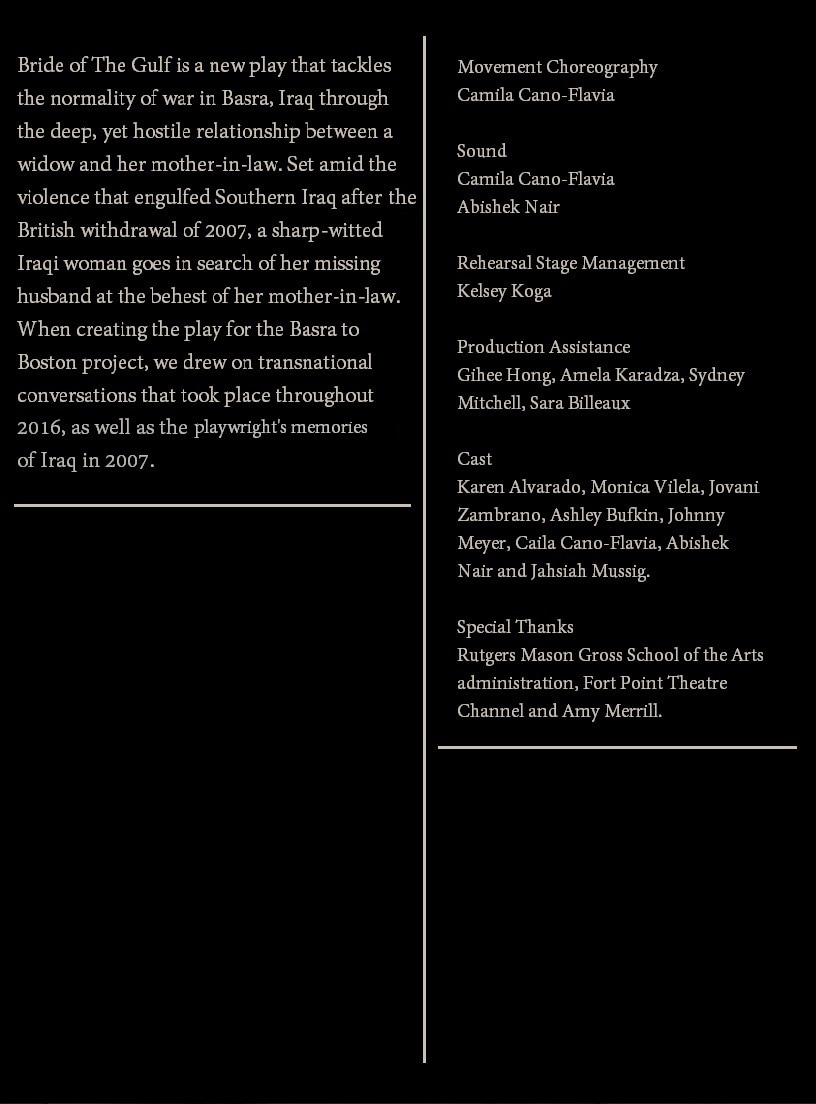

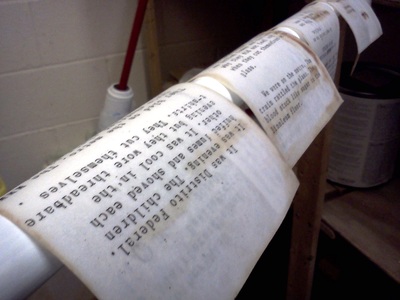

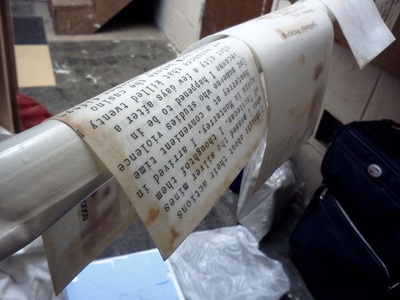

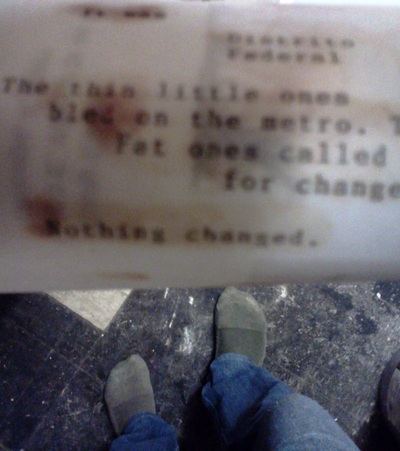

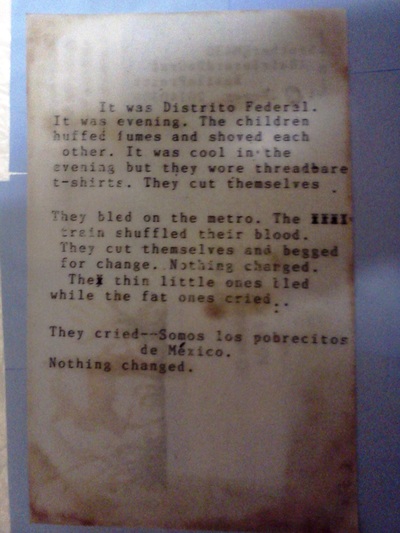

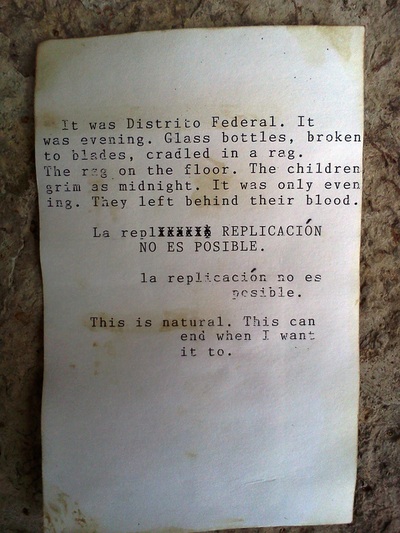

The staged reading takes place the Byrne-Reed House in Austin, Texas, at 7:30pm. Reception at 7pm. Discussion should wrap up by 10pm. This week, I had the privilege of staying at Rubber Repertory's Pilot Balloon Church-House. My partner, Karen Alvarado, was scheduled to come with me, but she had to go to NYC over the weekend for auditions. I missed her presence. But her absence compelled me to write a piece that tracks the contours of our feelings for each other. I suspect I will post more about that in a few weeks. In the meantime, I wanted to share some images from a very small project I worked on while I was here. As a part of Rubber Repertory's fundraising efforts, they offered their donors the opportunity to receive a piece of postcard art from the artists staying with them in Lawrence. The postcards presented a challenge, as straightforward writing felt inadequate for the medium--I write postcards all the time, and would never classify those as 'art.' So I experimented with a few new methods, so to speak, to earn my keep. The images below don't tell half the story, but I hope they will help me remember the work. The postcards I made were inspired by a handful of Mexican youths I saw on the metro near the Autonomous University in Mexico City; I watched them cut themselves with bottle glass and beg for pesos--but the passengers gave them nothing. Here's a partial list of materials: postcard, brother EM430 typewriter, milk of magnesia, club soda, soap, distilled vinegar, a memory of Mexico, a broomstick, a shower, a ceramic baking dish, absorbent paper, and a fourteen gauge needle that I brought back from Iraq. Many thanks to Rubber Repertory's Josh Meyer and Matt Hislope! I was lucky to have the opportunity to visit them in Lawrence! I am going to miss them, and the intensity of openness with which they listen to human experience.

Last night, two new landing pages went up on this website: 'Cryptomnesia' and 'Veterans' Voices.'

Cryptomnesia is the tentative title of a new play I am writing for the Department of Theatre Arts at Lawrence University. The play will go up alongside three other pieces: Antonin Artaud's SPURT OF BLOOD, Samuel Beckett's WHAT WHERE, and Caryl Churchill's THIS IS A CHAIR. When a new play is produced alongside other works, it typically appears in the company of other new plays; the experience of watching new work often elicits forced smiles and weariness, though a new piece can occasionally fire the imagination. The situation, in this case, is different. Artaud, Beckett, and Churchill are twentieth-century ogres, powerful and easily seen, mistreated but often admired for their strength. Of the three, only Churchill still lives. Artaud was loquacious on the purpose of art, but the other two typically remain silent. I'm writing Cryptomnesia, a short play that will appear at the end of the program. It would be very easy to fuck this up, but things will turn out okay. Promise. The other page describes Veterans' Voices, a program that I've been working on with Paul Woodruff. Paul comes from another generation. He served in Vietnam as a young Army lieutenant. He wrote plays as a young man, but ultimately focused on Greek philosophy, especially Plato and Thucydides. He studied at Oxford, earned a doctorate from Princeton, and then came to the University of Texas at Austin. After playing a pivotal role in the development of one of Texas' honors programs, he became the Dean of Undergraduate Studies, a position dedicated to improving the education of young students; this was an especially important task, because UT-Austin is a vast research university, and young people can easily get overwhelmed by the atmosphere. The purpose of public universities is higher education; active research plays a critical role in helping young minds ask and answer difficult questions, but it is also important to develop connections between young students and seasoned students--undergraduates and professors. Paul's work as Dean of Undergraduate Studies helped the university take major strides in building these sorts of relationships. He developed courses that ensured that young students have the opportunity to learn from professors who have a special gift for teaching. Paul also knows a great deal about Greek drama, having translated many of the tragedies and comedies of ancient Athens. His favorite modern play is Edward Albee's The Goat: or Who is Sylvia? Paul has written a number of plays. I am especially interested in two of them: Ithaca in Black and White and Geoffrey's Jerusalem. It is one of my goals to produce these plays. I am working with Paul on Veterans' Voices because it will help me reach that goal. What is Veterans' Voices? Since Paul and I have refused to incorporate the project into a non-profit, that is a little hard to pin down. But the main thrust is to communalize the cost of war at an emotional level. We do this through play readings, group recitations, story-telling, and (most importantly) listening. As playwrights, we try to tell the stories of others, and show how these stories reflect our life and times. As educators, we help place the experiences of individual people into the framework of a wider community. Sometimes, our purpose is classic catharsis. But other times we aim for pure expression. Paul's is a member of UT-Austin's philosophy department. As a philosopher, he has written three books for a wider audience: The Necessity of Theater: The Art of Watching and Being Watched, Reverence:Renewing a Forgotten Virtue, and The Ajax Dilemma: Justice, Fairness, and Rewards; I think these books help express our values. Paul and I are a value-driven partnership. If you start with values, and then look for opportunities as you happen upon them, then you have a pretty good idea of who you are going to be, even if you are not entirely sure of how you are going to do it. |

AuthorJ. M. Meyer is a playwright and social scientist studying at the University of Texas at Austin. Archives

December 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed